Many “F” words came to mind during our recent foray into the madness and magic that are Mexico City. No, not THAT “F” word. Well, perhaps once or twice, but only in passing. What came to mind: frantic, fantastic, but frequently frustrating. We’d heard a lot about Mexico City, its infamous traffic and pollution, and reputation for danger. A Latina friend even warned against taking or wearing nice jewelry. What we found was more nuanced. There was potential danger, yes, but more likely from being a victim of a traffic accident than a mugging, at least in the nice neighborhoods in which we found ourselves. As for the traffic…it truly was epic, unpredictable, very frustrating, at times nearly paralyzing the city and making it difficult to reliably make appointments on time.

That said, we found a lot to like: history, colors, textures, contrasts, culture and delicious cuisine, from high (Pujol, one of the 50 best restaurants in the world) to low (street taco culture and a burgeoning mezcal tasting scene). We ventured south under the auspices of MOPA (Museum of Photographic Arts, San Diego), benefiting from terrific advance planning and insider contacts in the contemporary photography scene.

Steve and I arrived a day early, as did Ralph and Gail, giving us a free day to explore, not to mention a head start on adjusting to the altitude of 7943 feet, which had me panting every time I climbed the beautiful spiral stairs of our boutique hotel, Las Alcolbas, in the chic neighborhood of Polanco.

Ralph and Gail were already settled in when we arrived, noshing at the street level restaurant, Anatole. For dinner, we had reserved a table at nearby Quintonil, which was excellent. Steve and Ralph elected the 6 course tasting menu, while Gail and I selected deconstructed smoked spider crab tostadas and shared a shrimp tamale with “chilpachole” sauce.

For our free day, we headed south to San Angel, to visit the shared homes and studio of Mexico’s most celebrated artistic couple, Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, Museo Casa-Estudio. This pair of outsized talents and personalities dominates the history of modernism in Mexico in the 20th century. Her tragic personal story and visceral artistic iconography graphically illustrate the expression ” to wear one’s heart on one’s sleeve.”

The Rivera-Kahlo compound is modern in its rectilinear esthetic, as well as its unusual his and hers organization. Two adjacent houses, red for Diego and blue for Frida, connected by a bridge, enabled Frida and Diego to have separate studios and living spaces. It was designed for them by Juan O’Gorman in 1931-32, and draws on Le Corbusier’s tenants. It was radical for its time in its simplicity, but even by today’s standard’s, its external floating spiral staircases are boldly modern. Its palate of bold color and surrounding cactus wall make it uniquely Mexican.

Its palate of bold color and surrounding cactus wall make it uniquely Mexican.

Diego’s studio contains many personal artifacts, as well as folk art collectables, including many Judas paper maché figures.

Conveniently across the street, just as we were ready for lunch, is the historic restaurant San Ángel Inn, set in a former Carmelite monastery dating to the 17th century. The beautiful gardens and elegant setting allowed us to rest our feet and recharge before heading out on foot to Coyoacán, following a route suggested to us by a TripAdvisor posting.

After a little jockeying, we located the “delectable cobbled streets” of the posting and the Plaza San Jacinto, where civic and store decorations were actively being prepared for Dia de los Muertos. Avenida Francisco Sosa was indeed “long but beautiful,” with attractive stores, courtyards, houses and gardens. The last home of Nobel Prize winning author and poet Octavio Paz drew us in, a beautiful compound of salmon and ocher, sheltering a quiet lush green garden.

Avenida Francisco Sosa was indeed “long but beautiful,” with attractive stores, courtyards, houses and gardens. The last home of Nobel Prize winning author and poet Octavio Paz drew us in, a beautiful compound of salmon and ocher, sheltering a quiet lush green garden.

Our first official MOPA trip function was that evening, dinner in the hotel’s renowned restaurant, Dulce Patria, helmed by Martha Ortiz. Thus began a thorough sampling of many delightful variations on mole, margaritas and guacamole (at Dulce Patria, the guacamole was enlivened with the bright surprise of pomegranate grains, while among the many mole options was a breast cancer research-honoring pink version).

Our first full day was an action packed one, beginning with a tour of Casa Luis Barragán, a World Heritage site and the celebrated modernist architect’s home from 1943-1988. The only disappointment: photography is prohibited. A NY Times article sent to us by Deborah after our return shed some light on the “intellectual property” issues being contested between the facility and its German owner, Vitra.

Traffic ate up much of our planned time for exploring the Centro Histórico, the Zócalo, also a World Heritage site. We had just enough time to duck into the cathedral, and to ascertain that the Palacio was closed for restoration, before lunch time at Azul Histórico. Here, the guacamole had its own distinctive crunchy touch: chapulines (yes, grasshoppers!). Fue delicioso!

I loved this space, a restored 17th century vice-regal palace. The dining is open air, sheltered by tall trees and anchored by a living wall of green, forming an attractive courtyard oasis of a center filled with boutiques, cafes, a Grupo Habita hotel (Downtown Mexico City) and a youth hostel. Several of us found souvenirs at Pineda Covalin, a boutique collaboration of two Mexican designers, Christina Pineda and Ricardo Covalin (I left with a pair of geode earrings, Becky found dolls for her granddaughters and Gail a scarf with Dia de los Muertos motifs).

The early evening was a meet and greet cocktail party welcome at Mexico’s City’s only gallery devoted to contemporary photography, Galería Patricia Conde, around the corner from the hotel. Many of the artists she represents were on hand to discuss their work. The variety was interesting. We enjoyed Laura Cohen’s photographs of smoke captured in glass vessels, as well as the imaginative, surrealistic, dreamy visionary constructed landscapes of Alejandra Germán. We also were quite captivated by the precious objects created by Patricia Lagarde, a veritable cabinet of curiosities of small ambrotype prints housed in a glass topped table. The very white Icelandic landscapes of Cynthia Araf were also visually stunning, very spare and minimal.

The long and full first day was capped off by a tasting menu with wine pairing in a nice room to ourselves at nearby Biko, another “Top 50” designated restaurant. It has a very spare blond wood Modernist look. Perhaps due to the wine pairings, I lost count of the courses after a while.

Day 2 was devoted to Hydra, a photographic cooperative formed by Ana Casas and Gerardo Montiel Klint, an effort to push forward and promote the work of contemporary Mexican photographers. About 1 year old, the nascent organization is finding its way forward in a relative vacumn of support for their work. For us, it was a whirlwind of visual overload, with 8 photographers presenting their work, broken up into 2 sessions, before and after a long lunch at Mexsi Bocu, around the corner in Roma Norte. Some of this work was dark and disturbing, both visually and topically, particularly that of Jose Luis Cuevas and Gerardo Montiel Klint. Cuevas is documenting a sect which calls itself “666,” followers of “jesuschristo hombre,” a televangelist broadcasting to Latin America from Miami. Gerardo’s large scale work of staged, gory, mutilated bodies was a ghastly metaphor for the ills of contemporary Mexican society. The work of former Magnum photographer Maya Goded documenting the lives of prostitutes was powerful. Alejandro Cartagena’s work charts the suburbization building boom being promoted by the Mexican government, as well as the consequences for workers now living far from their work, commuting in droves to work in the beds of pick-ups. Visual relief was provided by Mauricio Alejo, and Javier Hinojosa, with two very different bodies of work. Mauricio’s photographic and video work is very conceptual, making use of ordinary household items to reorder how one looks at space, while Javier’s black and white landscape work was simply beautiful, elegant and refined.

Our efforts to shake off the all-day-sitting cobwebs by walking back to the hotel were somewhat thwarted by the park between us and the hotel being closed off. Cliff, John and I finally hailed a cab, while Steve and Jon soldiered on on foot.

Dinner was on our own. My brief sampling on arrival of Anatole’s offerings made me want to sample it thoroughly, but the restaurant was closed, forcing us out into the neighborhood. We opted for casual, tacos at nearby La Casa del Pastor.

The following day was devoted to visiting Flor Garduño in Tepoztlan. In theory, Tepoztlan is only an hour from Mexico City. During the work work, it takes quite a bit longer to escape the clutches of the city. But it was well worth the trip. The town is an attractive colonial village in a valley, surrounded by hills.  Flor and her assistant Veronica were welcoming, with drinks and snacks ready in the garden. Her work is very feminine, often featuring nude women, many of them her friends.

Flor and her assistant Veronica were welcoming, with drinks and snacks ready in the garden. Her work is very feminine, often featuring nude women, many of them her friends. Her “studio” in Mexico is a grey painted open air garage, lending a soft light and featureless backdrop for her subjects, often using folk art or natural props from her garden or collection. Several additions were made to collections. We eventually made it to our lunch (“scheduled” for noon, arrived at 3 pm) at Posado del Tepozteco, a beautiful inn where we had a long table under an arbor looking out to a beautiful view of the town and temple ruins in the craggy rocky hills beyond.

Her “studio” in Mexico is a grey painted open air garage, lending a soft light and featureless backdrop for her subjects, often using folk art or natural props from her garden or collection. Several additions were made to collections. We eventually made it to our lunch (“scheduled” for noon, arrived at 3 pm) at Posado del Tepozteco, a beautiful inn where we had a long table under an arbor looking out to a beautiful view of the town and temple ruins in the craggy rocky hills beyond.

There were only 10 orders left of a last of the season special, chile en nogadas, but thankfully they hadn’t run out by the time it came my turn to order. I learned about this dish in Laura Esquivel’s Como Agua para Chocolate which I read in Spanish (slowly!) the year before, but was surprised to learn the symbolism of the colors and ingredients used to prepare it. Traditionally, it is made when pomegranates are in season. Roasted (green) chiles are filled with a sweet and savory picadillo filling (a mixture of pork, dried fruit and spices), covered with a white sauce made from nogadas (a type of walnut), sherry, milk and goat cheese and sprinkled with red pomegranate seeds. The green, white and red components of this dish reference the colors of the Mexican flag. The dish is labor intensive, and was invented by nuns in Puebla in 1821 to honor a visiting Mexican General, Augustín de Iturbide. I didn’t spontaneously ignite afterwards (as in the book), but I did have have an incredible sense of well being!

Most people were too pooped by the late lunch (which ended at 6 pm) and the drive back to Mexico City, to continue on with the planned day’s finale, a taco crawl and mezcal tasting. But I rallied, as did Christina, Gary and Zoraida, and Tom and Teri, and off with Natalia from EAT Mexico Culinary Tours we went to sample our way through Condesa. Our first target was tacos árabe from a tiny hole in the wall place, El Greco, where 2 small outside tables represented a large percentage of the seating. We had a few minute wait until the outside tables opened up. While I was peering into the place, my “huele bien!” comment (smells good!) elicited smiles from the man manning the meat spit and he shaved off a few samples to tide me over.

Natalia filled us in on the origin of tacos árabe and tacos al pastor, introduced into Mexican cuisine by Iraqi immigrants in the 1930s, again by way of Puebla. While Middle Eastern spit-grilled shawarma uses lamb (al pastor means in the style of the shepard in Spanish), the Mexican version uses pork, prepared with the same marination (with chiles, dried spices and pineapple) and vertical grilling technique. A pineapple is skewered above the layered meat, and its juices leaking down onto the rotating meat aid in tenderizing it. Tacos árabe consist of spit-grilled meat served on pita bread called pan árabe. The pastorero at work at the spinning spit is a blur of motion, slicing off crispy bits of meat onto the waiting tortilla below, then flicking a sliver of carmelized pineapple from the top, never missing the target tortilla down below. After being topped with chopped white onion and cilantro, an assortment of salsas and lime is available to finish off the taco to taste.

After fortifying ourselves with tacos árabe, we were ready to sample mescal at La Nacional. Mescal is related to tequila in that both are agave-derived distillates, but mescal is made from maguey agave, unlike the geographic implications and Blue Agave origin inherent in the name tequila. We tried tiny quantities of 3, each shot divided 6 ways. It must be an acquired taste-very searing, even sipping it. We were warned not to judge based on the first swallow, which is a shock to the palate, but Christina found she “couldn’t get past the first sip!”

We had no such trouble on our subsequent stops for more tacos, at Taqueria Los Parados for volcanes de queso and El Vilsito for tacos al pastor. Los Parados mean “standing” as in standing room only, and the corner open air taqueria was a bustle of comings and goings for munchy fixes, a fascinating cross section of society, from the unemployed (another meaning of Los Parados) to the well-dressed. The “volcanos of cheese” refer to the bubbling up of cheese on a tortilla placed on the hot grill. At our final stop, El Vilsito, no one had any difficulty getting past the first taco al pastor and on to a second! El Vilsito has a dual identity as a tacquería by night and auto repair shop by day (the two businesses are owned by the same family).

According to Natalia, the night was young yet-we were there at 10 pm or so, and on a Monday, a slow night. These taquerias reportedly become busier and busier the later the hour, going full swing at 2-3 am. We didn’t hang out late enough to witness this at first hand, but the activity we saw is testament to the enduring popularity of these Mexico City late night institutions.

Our final full day in Mexico City started with a trip to the lovely home (designed by her architect son) in Coyoacán of famed photographer Graciela Iturbide, also a former student of Manuel Alvarez Bravo (as was Flor Garduño). Graciela is diminutive, but with a quiet but compelling presence. Her short stature was countered by high top sneakers with a hidden high heeled wedge. Her home is filled with beautifully displayed collections of Mexican and other folk arts. Even the front window was visually fascinating, being covered with translucent botanical specimens to shield its resident from the street view (featured image). Graciela’s celebrated image of a female iguana vendor in a market, displaying her wares on her head and body, was the object of much commercial interest for multiple members of the group.

The negotiations completed, it was on to Frida Kahlo’s family home, Casa Azul, now the Museo Frida Kahlo. To try to squeeze it all in, we had decided the day before to forego a prolonged restaurant lunch in favor of a quick sandwich, which we ate in the colorful courtyard garden of the museum.  A documentary film we had viewed while at the Casa-Etudio on Frida’s life and career was terrific preparation for appreciating the unique artifacts on display of her life of physical disability and pain: a mirror installed on the canopy of her bed so she could see herself for self-portraits, her back-supporting, Medieval looking corsets, an easel mated with a wheelchair. Her demons, both physical and psychic, are unequivocably manifest throughout her notebooks, drawings and paintings.

A documentary film we had viewed while at the Casa-Etudio on Frida’s life and career was terrific preparation for appreciating the unique artifacts on display of her life of physical disability and pain: a mirror installed on the canopy of her bed so she could see herself for self-portraits, her back-supporting, Medieval looking corsets, an easel mated with a wheelchair. Her demons, both physical and psychic, are unequivocably manifest throughout her notebooks, drawings and paintings.

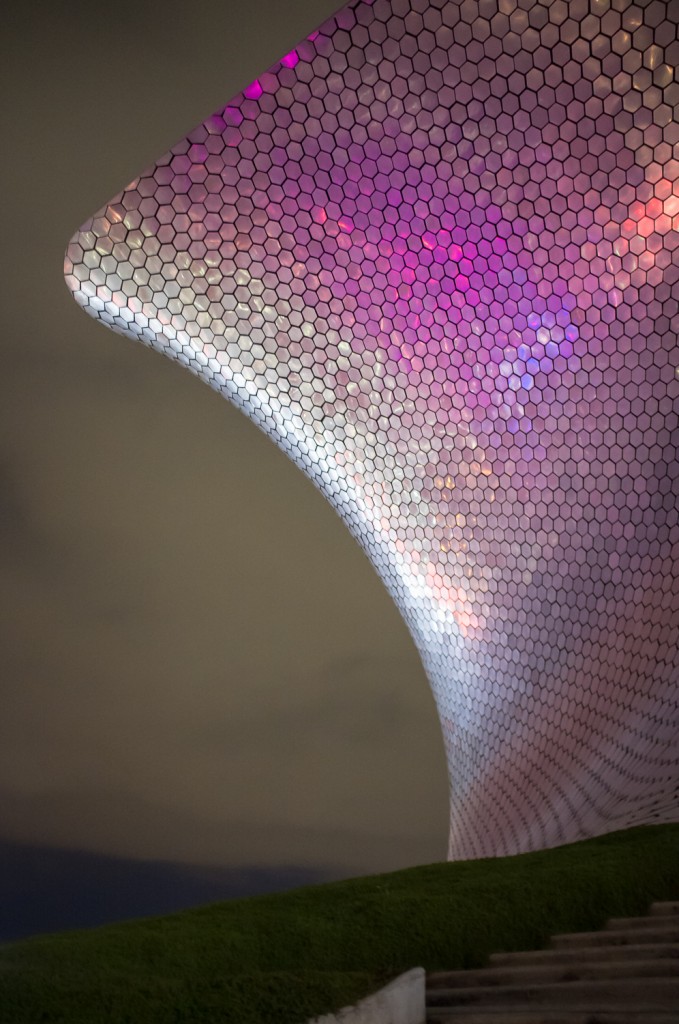

We were scheduled to see Televisa’s photography collection in the late afternoon, but this plan was foiled by traffic. A major thoroughfair, unexpectedly closed, squadrons of police on hand in riot gear, apparently in anticipation of a protest, thwarted our plans. A 40 minute trip turned into 2 hours and Televisa might take another hour to reach. So, we bailed. The silver lining was that this opened up a small window of time to walk to nearby Museo Soumaya, a new addition to the art scene in Mexico City.  A sleek metal sheathed curvy obelisk, it was built to house the art collection of Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim and named for his late wife. The shimmering surface of the building, covered by hexagonal aluminum tiles, reflects the sky and surrounding structures. Photographically, it is arresting, so much so for Steve that he never made it inside. A long spiral ramp recalls the Guggenheim as it winds up 6 floors to a light flooded sculpture gallery housing one of the world’s largest collections of the work of French sculptor Rodin. Reviews from members of our group who had proceeded me to the top and were winding their way down were unenthusiastic: “It’s like a truck loaded with Rodins dumped out its contents into a warehouse.” I had to agree that it wasn’t like the beautiful beaux arts sculpture courts of the Louvre or the Met, but I did find treasure in a pair of Tamara Lempika paintings. On other floors, I marveled at carved Asian ivory pieces and pre-Columbian ceramics. The Mexican modernist pieces of David Alfaro Siquieros were another highlight for me.

A sleek metal sheathed curvy obelisk, it was built to house the art collection of Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim and named for his late wife. The shimmering surface of the building, covered by hexagonal aluminum tiles, reflects the sky and surrounding structures. Photographically, it is arresting, so much so for Steve that he never made it inside. A long spiral ramp recalls the Guggenheim as it winds up 6 floors to a light flooded sculpture gallery housing one of the world’s largest collections of the work of French sculptor Rodin. Reviews from members of our group who had proceeded me to the top and were winding their way down were unenthusiastic: “It’s like a truck loaded with Rodins dumped out its contents into a warehouse.” I had to agree that it wasn’t like the beautiful beaux arts sculpture courts of the Louvre or the Met, but I did find treasure in a pair of Tamara Lempika paintings. On other floors, I marveled at carved Asian ivory pieces and pre-Columbian ceramics. The Mexican modernist pieces of David Alfaro Siquieros were another highlight for me.

Our final night culinary send-off was spectacular: Pujol, number 17 on the latest list of the world’s 50 best restaurants. It was within pleasant walking distance of the hotel, and we were seated around a large square table in a spare, but private dining room on the second floor. A pair of contemporary landscape photographs in the room were by a young photographer, Pablo López Luz, who we met a few days earlier at Hydra. We again opted for the wine pairing. The 10 courses were beautiful and delicious, and at 794 pesos ($61 US), a bargain for the presentation, variety, and deliciousness. Two dishes were particular standouts. One is a play on the street corner standard, elote (corn). Pujol’s version is baby corn served steaming in a gourd, enriched with coffee infused mayonaise, dusted with chicatana ants. Yes, insects appear with some regularity on gastronomic menus in Mexico City, although both times we probably wouldn’t have known but for the menu descriptions. The madre mole was also unusual in that it was served virtually by itself, a circle of mole concealing a small corn tortilla, not adorning chicken or any of the usual suspect vehicles. This focused one’s attention on its creamy richness and the delicate balance achieved between sweet and savory. The mole was described as being continuously added to, akin to a starter used for bread-making; that is, a batch isn’t made, served, finished and then remade, but is continually being “extended.” What we were served was some 200-plus days in the making, or perhaps better, evolution.

On our final morning, there was just enough time to enjoy a last delicious breakfast at the hotel (I alternated daily between the cazuela, fluffy eggs baked in a tortilla with a souffle like texture, with scrumptious mole, and the enchiladas suizas (chicken enchiladas in an addictive green chile sauce)) before sprinting off for a too-short-but-better-than-nothing, couple of hour introduction to the one of the world’s biggest and best anthropology museums, Museo Nacional de Antropología. It was huge, on the scale of the Met in New York, and staggering in its pre-Columbian statuary and other holdings. Like the Met, it clearly is too vast to be conquered in one visit, so I regretfully had to consider my first visit reconnaissance prior to a return visit I’m already mentally planning. Sadly, there wasn’t time to visit the Museo de Arte Moderno and the Museo Rufino Tamayo, both tantalizingly close-by, but not to be on this already tightly scheduled and action packed introduction to the dynamic culinary and cultural cauldron that is Mexico City.

Wonderful comments and photos! Thank you for helping me relive a wonderful trip.

And thank you for being a part of it-you are my first official blog commenter!-marie

Hello Marie,

I have just found and read your post, after so much time. I enjoyed it a lot! I like the photo you took of Flor, Deborah and myself. Thanks!

Verónica