In recent years, I developed a serious case of Whale Obsession. It started innocently, snorkeling with humpback mothers and their calves.

Their tender care and interactions are mesmerizing, so much so that we’ve devoted 3 trips to swimming with and photographing humpback whales. Our first humpback trip was in 2007, with Bob and Debbie and Nancy and Gerry, to Silver Bank, between the Dominican Republic and the Turks and Caicos. This is where humpback mothers congregate in winter months (January-March) to give birth in warm and shallow waters, staying long enough to allow their calves to nurse and grow strong enough to make the long northern migration to their summer feeding grounds in New England. Even the broken rib I carelessly sustained (fiddling with my camera when a wave pushed me onto an unyielding corner of the boat) could not keep me out of the water, as painful as it was to kneel on the gunnel of the skiff suspending my camera in mid-air. In 2019, I returned solo to Silver Bank, taking a single female spot on another trip run by a friend, professional underwater photographer and trip organizer Tanya Burnett.

In the ensuing years, we had devoted another trip in 2013 to snorkeling with whale sharks in Isla Mujeres, Mexico (okay, technically, whale sharks are a large carpet shark and thus are large fish, but being filter feeders, they can be compared to baleen whales).

We devoted a delightful segment of a 2019 trip to French Polynesia to fly to Rurutu in the Australs for more water time with humpback mothers and calves.

I finally persuaded Steve last year to do a trip to San Ignacio Lagoon in Mexico to visit gray whale mothers and calves. Part of his reluctance was the relative inactivity of the trip, being confined to a boat, as swimming is not permitted in the sanctuary.

Steve seemed to enjoy feeling the “chubby rubber” feel of a gray whale, even if entering the water is prohibited in the San Ignacio lagoon sanctuary.

At last year’s Sedona International Film Festival, we were scheduled to see a documentary called Patrick and the Whale, about one man’s obsession with a particular sperm whale he calls Dolores. Unfortunately, Steve developed flashing in an eye, so we had to leave earlier than planned so he could have it evaluated. Subsequently, I never was able to find the film for streaming. But somehow, a seed was planted…

Our friends Nancy and Gerry and Bob and Debbie had done a sperm whale trip to Dominica years back. Somehow, back then, sperm whales seemed to me just not as appealing or attractive as humpback whales, although I did find their habit of sleeping suspended vertically in the water intriguing.

Dominica: Sperm whales suspend themselves in the water column to sleep. Their sleep sessions are short, 10-15 minutes. Sperm whales are the only cetaceans known to sleep in a vertical posture. Amazingly, this behavior was first reported in 2008. Researchers affixed suction cup monitors to 59 sperm whales, recording their periods of inactivity, which amounted to 7% of the day. Like dolphins and some birds, their sleep is uni-hemispheric slow-wave sleep, with one half of the brain asleep and the other half presumably vigilant.

Partial blame for my recent whale obsession may lie with the Extraordinary Attorney Woo, a Korean TV show I loved in 2022, featuring an autistic young lawyer with a full-blown case of Whales on the Brain.

The only way to slake this thirst is direct contact. In the spring of 2023, following on our gray whale trip, Steve, Greg and I signed on with our friend Cindi LaRaia, Dive Discovery travel specialist, to travel to Dominica in January 2024 to snorkel with sperm whales. We took 3 of the 5 spots and tried to fill the remaining 2 with like-minded friends. I was surprised this proved fruitless but many of our friends (Bob, Debbie, Nancy, Gerry, Phil, Garid, Lauren, Brad) either already had done similar trips or had other travel plans. Ultimately, a couple from the San Francisco Bay area signed on, Danny and Julie, who proved to be wonderful additions. Initially Cindi offered two 5-day back-to-back trips, but ultimately ran only the first and consigned the second to another group leader, Caine Delacy, who runs predominantly snorkeling trips, with whales in Dominica and elsewhere. One difference we noted between trips is Cindi runs her trips with a total of 6 people, including herself (up to 4 people can be in the water at a time), while Caine and others have a total of 7-8 people on their trips.

These trips are not cheap at $7000 per person and there are no guarantees when it comes to wildlife. This was for 7 nights accommodation (including breakfast, about $300/night) and 5 days on the water in a boat with an experienced operator, Pernell Francis, with the all important permit (only a few are issued by the government each year and they are limited to a maximum of 8 people per group). For airfare (first class one way, since we’re old and it was a red eye!), tips, transportation for excursions and dinners, we spent at least another $4000. As our Iceland guide and friend Byron Conroy characterized this type of trip, these are “high risk, high reward” ventures. We were familiar with the no guarantees aspect of these type of wildlife safaris, having been largely skunked on a sardine run in South Africa in 2009 (organized by Cindi, with Nancy and Gerry and Bob and Debbie). As I remember it, we devoted 10 days to the sardine run on the Eastern Cape resulting in 45 very exciting minutes with a bait ball, with Cape gannets and dolphins slicing through the frenzied mass of fish. Of course, we were tortured by reports from the groups that followed us, with videos showing Bryde’s whales gobbling up giant mouthfuls of sardines.

We also were skunked on another bait-ball-based attempt to photograph sailfish in Isla Mujeres in 2014. So, we tried to prepare ourselves for the possibility of bubkes.

Physeter macrocephalus, the sperm whale, would be the sole focus of this trip. Although sperm whales can be found all over the world, there is a resident population of predominantly female and young sperm whales who live year round in Dominican waters. Estimates of their numbers range from 200-500, declining at a rate of 3%/year. Large males migrate to these waters at this time of year to mate.

Cindi led one prior trip like this, in November 2021, when the island reopened from Covid lockdown, and hoped to see a large male on this trip. Her prior 5-day trip had been plagued by reopening difficulties, including engine trouble on the boat. Their first 3 days they saw no whales and had only a quick fly-by on the 4th. They were rewarded for their patience on their 5th and final day. Thus, we tried to temper our expectations. Thankfully, our luck held and we spotted whales on 5 out of 5 days! Three of these days were good and two were off the charts amazing. Caine’s first group of 2024, which followed us on Pernell’s boat, was skunked on their first day out when the wind kicked up.

Our days were structured along these lines:

We met for breakfast in Hotel the Champs open air dining terrace at 7 am, having pre-ordered our selections the night before. I usually went for a single egg scrambled with vegetables and a piece of French toast, with fruit. This was a half portion, after the first morning when we realized the portions were enormous.

The lovely view north from the dining terrace of Hotel the Champs. Hurricane Maria in 2017 was not kind to Dominica, with 95% of structures losing their roofs.

Speedy G came to fetch us at 7:45 am to ferry us down the hill and north along the coast to the Portsmouth dock, about 15 minutes away. We came to rely on Speedy to ferry us around the island to dinner and excursions. His Toyota Voxy van was distinctive, with a broken driver’s side window protector edged in a jagged shark’s tooth pattern and the back window emblazoned with What Must I Do to be Saved? in large green letters.

Boat captain and sperm whale whistler Pernell and deckhand John were already at the Aria to receive our gear before we stepped aboard.

At the dock, Steve, aka Mr. Whitey White, trying not to become Mr. Pinky Pink under the Dominican sun.

We pulled out necessary gear (wetsuits, snorkels, masks, fins) and stowed our bags in the dry cabin below. There was a toilet down below but Pernell noted that in his many years piloting this vessel, he had never seen anyone use it! Cindi had arranged for Pernell to pick up catered lunches for us, which we usually ate as the boat headed back to the dock.

Before we arrived, we’d received notice that Dominica’s Fisheries department had specified that our whale days were to end at 2 pm (instead of 3 pm) and that no free-diving was allowed. Greg is a good free diver and this decision caused at least him some consternation, although ultimately didn’t prove to be too catastrophic to our photography. The basic injunction was that if our fins went up, our time in the water would stop.

From 8 am-2 pm, the search was on. Usually, Pernell would stop a few times, put on headphones and listen with a directional hydrophone in the water for a clue as to the whale’s whereabouts. We never struck on the first or second listen, but eventually, he’d pick up some clicking to point us south. He also checked in with whale-watching boats and kept an eye on the water for blows, which on a sperm whale is just to the left of midline and angled forward at 45 degrees.

Pernell was expert at positioning the boat in the path of the whales. Only 4 people can be in the water at a time, so we divided up into two groups of 3 for staggered entries. We tried to enter the water as quietly as possible, fins pointed down and once in the water, looked back to the boat for which direction to swim. Sometimes Pernell would halt our mad dashes, screaming “Let them come to you!” We’d strain our eyes with our necks on swivels, trying to fathom where they’d appear, initially vague gray shadows, quickly becoming larger and larger until, all too soon, they were past us. Sometimes, the whales wanted nothing to do with us and finding us in their path, would dive down below us. A rare whale would loll on the surface, seeming curious. The whales also seemed less inclined to dive down away from us when they were in a group. If a whale did a deep dive, we’d pick up and look for another whale or group to swim with, as a deep diver, presumably on a feeding run, usually wouldn’t reappear for 45 minutes or so.

The sperm whale’s large head is mostly nose and occupies up to 1/3 of its body length. Behind the eye is the tiny ear. It doesn’t have a true dorsal fin, although the largest of a series of dorsal ridges resembles one.

Our encounters could be brief (15-30 seconds, fleeting glimpses) to prolonged (15 minutes or more). The whales set the pace, sometimes leaving us in their wake unceremoniously, other times swimming at a more leisurely cadence that we could keep up with, at least for a while. It was both exhausting and exhilarating. When it was clear they were leaving us behind, we’d stop swimming, regroup and the boat would approach. Over and over, we’d sprint, strain our eyes and hope, swimming back to the boat when the encounter was over, to hand up our cameras and fins and pull ourselves up the ladder at the back of the boat to gladly do it all again. I was comfortable in the warm water in a 3 mm wetsuit, with a hood and gloves (more for sun than warmth), with scuba socks and snorkeling fins. Cindi brought along long Cressi free-diving fins but her feet were rubbed raw enough after a few days that she was happy to borrow the SCUBA booties and split fins I brought along as back-up (in case the foot of my aging Atomic snorkel fins tore).

The photography for the sperm whales was relatively simple, all available light. The animals are too large to cover with strobes. I used my widest angle setting (14 mm) and could have used even wider if I had. Once I had the settings dialed in, there wasn’t much need for adjustment, usually ISO 400, f-8, 1/125 shutter speed. When we had the opportunity (not always possible), having the sun to our backs provided the most pleasing results.

Tuesday, January 2-Wednesday, January 3, 2024

As Steve and I were taking a red eye to connect to a flight to Dominica in Miami, I splurged for first class tickets going. Unfortunately, this did little to alleviate the misery of a cold 4.5 hour overnight flight, arriving at 6 am to a surprisingly chilly Miami. Despite a long walk to the Centurion Lounge, it was uncomfortably frigid there too. We met up with Cindi, Greg, Danny and Julie at the gate.

The flight to Dominica is about 3.5 hours. At least for Steve, Greg and me, seated in 3 of the 4 first class bulkhead seats, our flight was enlivened by our seasoned cabin stewardess, who graphically described the approach to the Dominica airport thus: First, we line up between two mountains, then we make a left turn, then follow a river valley to the airport (which has a short runway). As she said, the rain forest did appear close enough for us to reach out and pick coconuts. The challenging landing requires special training, as the auto-pilot must be disengaged and the plane flown manually, avoiding the mountainous terrain and jungle. This pilot’s perspective Youtube shows the approach. Chatting with Caine after our trip, he mentioned he doesn’t take the American Airlines flight into Dominica anymore, as he’s had a number of clients whose flights have been unable to land, which can happen if there are clouds or fog which obscure the visual landmarks on which the pilots rely to align the plane for the approach.

After settling in at Hotel the Champs and meeting owner Lise, who immigrated with her husband Hans to Dominica 17 years ago after stints in the Netherlands, Paris and Barcelona, we built our underwater cameras, organized our gear into mesh bags and relaxed over dinner on the open air terrace of the hotel. There was an intriguing item on the menu, one I’d never sampled: lionfish, served in a white wine sauce with rice and vegetables (it was delicious). Lionfish are a scourge in the Caribbean. In the Indian and Pacific oceans, their numbers are kept in check by predators, including larger fish (groupers), moray eels and sharks. In the Caribbean, to which they were introduced accidentally, their numbers are unchecked and their voracious appetites are decimating native species. They reproduce at alarming rates. Lionfish on the menu are one of the efforts to combat this phenomenon. Unfortunately, they can’t simply be collected in a net but must be individually speared, as we had seen our Cuban dive guide do.

Lionfish are beautiful in the Indo-Pacific, where they belong (Raja Ampat, Indonesia). Their venomous spines make handling them as potential meals treacherous.

Thursday, January 4, 2024

Having been thoroughly skunked on a few marine life safaris before, I went prepared for long hours of waiting, bringing along my Iphone loaded with electronic books and AirPods, just in case there was a lot of downtime. Happily, after several listens and repositioning, we eventually found a male sperm whale. Pernell said Jonah was probably about 8 years old.

Our first glimpse of a sperm whale was of its underside! The white outlines its narrow jaw and the small pectoral fins are tucked close to its streamlined body.

He was eventually joined by his little brother.

A pair of sperm whales in the Dominican waters beneath us. The notches in the larger whale’s tail are acquired (shark bites, possibly?) but help whale operators and researchers to identify individual whales at the surface.

We had multiple short swims, usually going in three at a time with one really long encounter, during which I found myself virtually alone over a vertically positioned whale. Unfortunately, at that moment, I was taking in a lot of water through my snorkel. Eventually, I got that straightened out and was able to swim with the whale when it again assumed a vertical, stationary sleeping posture in the water.

We were exhilarated by our first day success and elected to stay in at the hotel for dinner, where I enjoyed the eggplant parmigiana on offer that evening.

Friday, January 5

Arriving to breakfast a few minutes after 7 am, Danny and Julie were already there. Their faces were drawn, as they had been awakened in the middle of the night by the news that Danny’s 89 year old father had died in Taiwan, where he had been visiting a hot springs resort with one of Danny’s brothers. He collapsed and couldn’t be revived. They had spent the early morning hours making plans to depart as soon as they could to make their way to Taiwan. The American flight we had come in on isn’t offered every day. They had worked out a prolonged itinerary which would take them, by way of a series of circuitous Caribbean hops, to New York, where they could catch a 17 hour non-stop to Taipei. Since they couldn’t leave until the evening, they came out with us on the boat.

At the breakfast table with Greg and Cindi, I couldn’t help but think back to our trip together in 2019 to French Polynesia, when we learned in Rangiroa that Greg’s father had elected palliative care. He’d been ill before the trip but had urged Greg to go. Greg decided to cut the trip short and didn’t come with us as planned to Fakarava, but had to wait two days for the next flight out to Papeete. His father died on the morning Greg was starting back to the US.

Pernell’s listening sessions on the hydrophone were fruitless. Eventually, we found ourselves all the way at the south end of the island, where we had a series of brief encounters with members of a family, including Digit, Fingers and Knife. Our best encounter of the day was the last, a close swim-by with Pinchy, so close my 14 mm lens could not include all of her.

Dominican tete a tete, Greg and Pinchy the sperm whale look close enough to touch from my angle. They actually were about 6 feet apart.

We said goodbye to Danny and Julie on our return to the hotel after a satisfying day on the water. Given how short they had to cut their trip, we were especially happy that they had been encounter-filled days. It’s strange how things work out…the hotel was oversold with some of Caine’s group coming in early for their follow-on trip, overlapping with us as we stayed over another day after our whale swims (to catch the American flight out to Miami, not offered every day). Lise and Hans were going to have to vacate their home to accommodate all of the reservations. With Danny and Julie’s early departure, the hotelier’s problem was solved and Lise indicated she would refund them a portion of their stay.

We decided to go out for dinner, a decision we came to regret. Speedy said Keepin’ It Real, the further away of two local lobster restaurants, was better. Although we had a reservation, it was severely understaffed. We milled about without a clear check-in person materializing. The music was obnoxiously loud, the tables not bussed. The staff was friendly but we probably blew it by ordering our meals with a different server who came by, so that when our original server stopped by, they thought our order was already in. It took over an hour to have our order taken. One way or another, it was pretty clear we were forgotten. We were texting Speedy to pick us up when the meal arrived. It was tasty, at least the multiple side dishes were, which accompanied the well-seasoned but over-cooked lobster.

Saturday, January 6

What a day!

So much of the sperm whale’s anatomy is visually puzzling, seemingly disproportionate, from the huge head (the macrocephalus of the scientific name), the comparatively tiny eye set so far back, the small pectoral fins. Their brain is the largest in the animal kingdom, six times larger than homo sapiens. Much of the large head is occupied by the spermaceti organ, filled with a substance resembling sperm (hence, the name) which drove men in the Industrial Age to nearly wipe out sperm whales in the quest for this fuel, used to light lamps, as an industrial lubricant and to make candles. The spermaceti organ and its waxy contents are employed by the whale in echolocation, enabling the whale to hunt and locate prey at lightless depths.

The day started much as the two preceding ones had, with several “all quiet” listens by Pernell and motoring to the south. We ultimately found a trio (Pinchy, Fork and Fingers) and had an excellent head on encounter.

We were surprised when Pernell pulled us off this sure thing, but he received a call from a whale watching boat further south that was on a large group, with a male. What we found blew us away! This group was made up of members of 3 families, including A1 and A2. Greg counted 15 individuals, including babies, young males (penises protruding, probably adolescents) and females. It was incredible how closely they let us approach and how slowly they swam, at a rate we could match. At one point, I was watching an aggregation of whales to my left when suddenly a large whale came in on my right, close enough I screamed into my snorkel. Steve actually was contacted by a tail and Cindi had to gently ease herself out of a trio which came up underneath her. Some individuals stayed vertical in the water for prolonged periods, as we hovered on the surface.

We saw the Dominican sperm whales seem to repeatedly affectionately mouth or gum each other. The dangling white line protruding from the open mouth isn’t fishing line, as we first thought, but tentacles of giant squid.

Mother and calf sperm whales in the beautiful blue waters of western Dominica. The scratches on the head of the mother are presumably from giant squid encounters. Calves are left in the care of aunts when mother sperm whales descend to the depths for 45 minutes or more to feed.

A sperm whale calf in Dominica eyes me curiously from the safe shelter of an adult female, which may be its mother or an aunt.

Do I have something in my teeth? The sperm whale equivalent of broccoli, a dangling giant squid tentacle is evidence of a recent meal.

Back at the hotel, we did a quick turn around to go out again on an Indian River float. Speedy picked us up and drove us down the hill, where Eric Spaghetti rowed us down the calm green ribbon with luxuriant jungle growth of palms, bamboo (imported from Tahiti) , wild ginger, with sightings of giant egrets, herons, a giant indigenous iguana and white crabs at the river’s edge.

It was a gorgeous golden afternoon for a leisurely float down the lush Indian River, near Portsmouth, Dominica.

Does this look familiar? This rustic structure along the Indian River in Dominica was built as a movie location, seen in the second Pirates of the Caribbean film franchise.

We saw an attractive array of birds:

We did see a scary sighting on the otherwise peaceful and idyllic Indian River and I don’t mean the pasty white tourists in other boats. I refer to this large indigenous iguana:

A startling sighting on the placid and verdant Indian River in Dominica: an iguana with a distinctive punk sensibility.

Those flesh-colored protrusions under the chin of this Dominican iguana are not teeth, as terrifying looking as they are. This is the Lesser Antillean iguana (Iguana delicatissima), a critically endangered endemic species. Pressures on the species include competition for habitat with the introduced green iguana, feral animal predation and hybridization with the green iguana. On Dominica, the invasive green iguana arrived with relief supplies after Hurricane Maria in 2017.

There is a short trail running along the Indian River, accessible from the Bush Bar, where brilliantly red ginger grows profusely.

Cindi found a bamboo hand-carved incense burner for the many varieties she brought back from her recent trip to the Indian sub-continent. We all marveled at the strength of the jungle juice in tiny white paper cups served at the Bush Bar on the river.

We walked back, a steep climb up the hill. Speedy had driven us down for free, probably betting that we would call him for a ride back rather than climb the hill.

Rain broke out at dinner at the hotel, which was as drawn out as the night before. The hotel seemed to have filled up and most of the tables were occupied. I enjoyed my coconut curry vegetable dish with rice and Steve and Greg both had the pumpkin soup and chicken pizza. Cindi’s pork was large, tough and not appreciably Thai. We learned later from Lise that most of the diners were locals, out for Saturday night.

Sunday, January 7, 2024

The wind picked up today, enough we thought it might have been problematic for seasick-prone Julie. Remarkably, Greg was managing without his usual arsenal of Scopolamine patches. It wasn’t too rough, just a contrast from the glassy seas we had enjoyed the past 3 days.

Our first encounter today was our best of the day, a prolonged horizontal hang with a sperm whale at the surface. We were amazed it didn’t dive as we closely approached, as did the whales on our subsequent encounters.

Our final encounter was with a group of 4 whales, who promptly dove into the depths, hanging vertically, one after another.

We went out to the Intercontinental for dinner, an elegant and more expensive option, but quiet and comfortable on a patio table (except when the sliding wall of glass was left open and too much air conditioning escaped outside!). We shared a beet hummus to start, with Caesar salads and for entrees, enjoyed shrimp fettuccine (Cindi), beet risotto (Greg and me) and pappardelle with meat sauce for Steve. The coconut ice cream didn’t have a hint of coconut. Our best guess was vanilla, but Greg didn’t think it even had much vanilla flavor to it.

Monday, January 8, 2024

Sperm whale babies are cared for in family groups, including their mother and aunts and may be suckled by an aunt in addition to their mother. Gestation is long, 14-16 months, single and separated by years (4-6 on average, up to 15 years known). With the mouth open, the narrowness of the jaw can be appreciated, as well as the conical teeth.

I’d have a tough time picking out a single favorite sperm whale image from this trip to Dominica but this portrait would surely be a contender.

This sperm whale in Dominica seems happy to see me! The lower teeth are conical, while the upper are not erupted and appear as reciprocal pits. Notice the scratches and circles on the chin, souvenirs of a struggle with their favorite food, the giant squid, which they hunt in the ocean’s dark depths. Sperm whales can dive thousands of feet deep and have been recorded deeper than a mile (2 km). They can stay down as long as 2 hours but on average, although most dives are 45 minutes to an hour.

What a finale day! Wind was predicted and Pernell thought it would be “rough and unpleasant”. It was choppier and a little more dicey pulling ourselves up the ladder back onto the boat, but overall, it wasn’t bad. Even usually seasick Greg managed without Scopolamine, declaring that he had his sea legs.

We had plenty of reasons to plunge into the water again and again, namely groups of 3-5 whales, who sometimes let us closely approach. Experience a VERY close interaction vicariously here.

Two babies, the one in front accompanied by a young male (front large whale with positive penis sign visible), maybe an older brother. Sperm whale pods are matrilineal, consisting of females and their young (male and female), with males staying until adolescence (varying from age 4-20) when they begin associating with loose bachelor groups . Adult males generally lead solitary lives, returning to areas like Dominica to mate.

Sperm whales maintain close contact with each other in the beautiful blue waters off the west coast of Dominica. For scale, the remora (white fish) on the vertical whale is 2-3 feet long.

Greg’s shot of me with a family of sperm whales residing in Dominican waters, a bevy of gentle giants.

A spent, but satisfied group of sperm whale admirers: Greg, Cindi, me, Pernell Francis (our boat captain and chief whale whisperer) and Steve.

On our return, we arranged transport via Speedy for an afternoon hike at Cabrits National Park. We’d been seeing the imposing restored red brick Georgian style buildings of Fort Shirley prominent on the slopes of the leafy peninsular headland every morning as we set out from the dock into Prince Rupert Bay.

Fort Shirley, overlooking Prince Rupert Bay, at sunset. African slave soldiers of the 8th West India Regiment revolted here in 1802, taking over the garrison for 3 days, leading in 1807 to slave soldiers in the British Empire being freed. The British built most of Fort Shirley, although the French made additions during their occupation of Dominica from 1778 – 1784. The garrison was abandoned in 1854. Restoration began in 1982.

The peninsula is the remains of an extinct volcano. The East Cabrits trail was largely covered and led up to a viewpoint where we could also see Douglas Bay. The views were magnificent.

Cabrits National Park: This peninsula was once an island. Volcanic flows joined it to mainland Dominica.

Steve took advantage of our solitude to launch the drone. From there, we could see our dinner destination, the Intercontinental, where Greg and I enjoyed roast chicken with cous cous, Steve and I split a chopped salad, and we all shared the beet hummus. Cindi’s hamburger was an overdone disappointment. We were not tempted a second time into ordering the house made ice cream.

Tuesday, January 9, 2024

What a difference a day makes! The hotel filled up with a group traveling with Caine Delacy. Sperm whale permits are for 10 days. Cindi had initially offered two 5 day back to back trips, but after filling ours, consigned the second 5 day trip to Caine, who offers a series of consecutive trips each year. At breakfast, we could easily see whitecaps. Their group wasn’t able to venture out beyond the protection of the island and didn’t see any whales their first day. The permitting is strictly controlled. After Julie and Danny had to leave early, Lise asked us one day if we would mind taking out with us a staff member of hers for her birthday. We had no objection and Lise said “She will be thrilled.” But when we asked Pernell, he said this was a no go as he had had to report exactly who would be on the boat and when and no substitutions were possible.

We took it easy in the morning. Speedy picked us up at 1 pm and we careened up the winding steep and narrow road on the slopes of Dominica’s tallest mountain, Morne Diablotin, to walk on the lovely, cool and covered Syndicate Trail and a segment of the island-long Waitukubuli National Trail. The Syndicate Trail showcases the tropical rain forest, with towering trees, huge prop roots and vines. The trail is so lush, it was hard to believe the trees were stripped bare by Hurricane Maria in 2017. It appears fully recovered.

We speed-walked the trail, not realizing it is a loop, so probably picked up some extra mileage there, trying to make it back to the Visitor’s Center by 3 pm, as we’d arranged with Speedy. However, he had gone in search of something to eat and returned closer to 3:30 pm. Down the mountain we sped, Speedy honking to warn oncoming cars at every hairpin turn. The road is so narrow and curvy, it brought Maui’s famous road to Hana to mind.

Although Lise and others looked skeptical at our leaving “so late”, our timing (in my opinion) was perfect for photographing and experiencing Syndicate or Milton Falls. The parking area is a virtual garden, planted with colorful array of flowers. A $5 per person entry fee (the access is on a private farm) allowed us to walk to the falls, which was completely shaded (very even lighting) in afternoon. A few shallow river crossings were required. Cindi opted to walk in the water, while the rest of us tiptoed over stepping stones. This excursion justified my hauling a tripod and neutral density filters to Dominica!

Dominica’s Syndicate Falls, also known as Milton Falls, is reached by a short walk and several stream crossings. The river was low (ankle deep) this time of year.

The walk back from Syndicate/Milton Falls along a verdant river corridor, glowing in the late afternoon.

We had our final dinner at the hotel, Cindi having the coconut curry shrimp and Greg and I opting for a vegetable version.

Wednesday, January 10, 2024

Since we weren’t leaving until the afternoon, we had just enough time to visit a we-can-dream property we’d been admiring from the boat, as we traversed the west coast of Dominica each day: Secret Bay, a Relais et Chateaux, with fractional and villa ownership and a citizenship by investment option. It was, in several words, drop dead gorgeous!

Sperm whales have been occupying the forefront of my brain since our return. The more I learn about them, the more astounding they are, from their anatomy, their family structure, even their responses to being hunted and pursued. That enormous brain, the largest in the animal kingdom? Reviews of open whaling boat logs indicate that within a few years of the onset of commercial whaling of sperm whales, successful kills dropped 60%! What can explain such a statistic but that sperm whales were catching on and spreading the word to their compatriots? Estimates of the world-wide population vary widely. It is thought there were at least 1 million, possibly upwards of 2 million, sperm whales in pre-whaling times, with 1 million killed during the peak whaling centuries. There may be as many as 700,000-800,000 sperm whales now by some estimates, with others suggesting the population is a more sobering figure of approximately 300,000.

Leading up to this trip, I listened to many hours of Herman Melville’s 1851 classic Moby Dick , in half hour spurts while driving to work and cleaning up the dinner dishes (the audiobook version is almost 25 hours long!). A huge male sperm whale (reported to be 85 feet in length) actually did ram a boat in the Pacific in 1820. The accounts of a few of the survivors of the ill-fated Essex, who had to take to the sea in their open whale boats with meager provisions, inspired Melville’s whale tale of an obsessed Captain Ahab who pursues the white (sperm) whale he believes cost him his leg. Melville did spend time working on a whaling ship as a young man. Something I noticed after starting the book: Moby Dick is referenced literally everywhere!

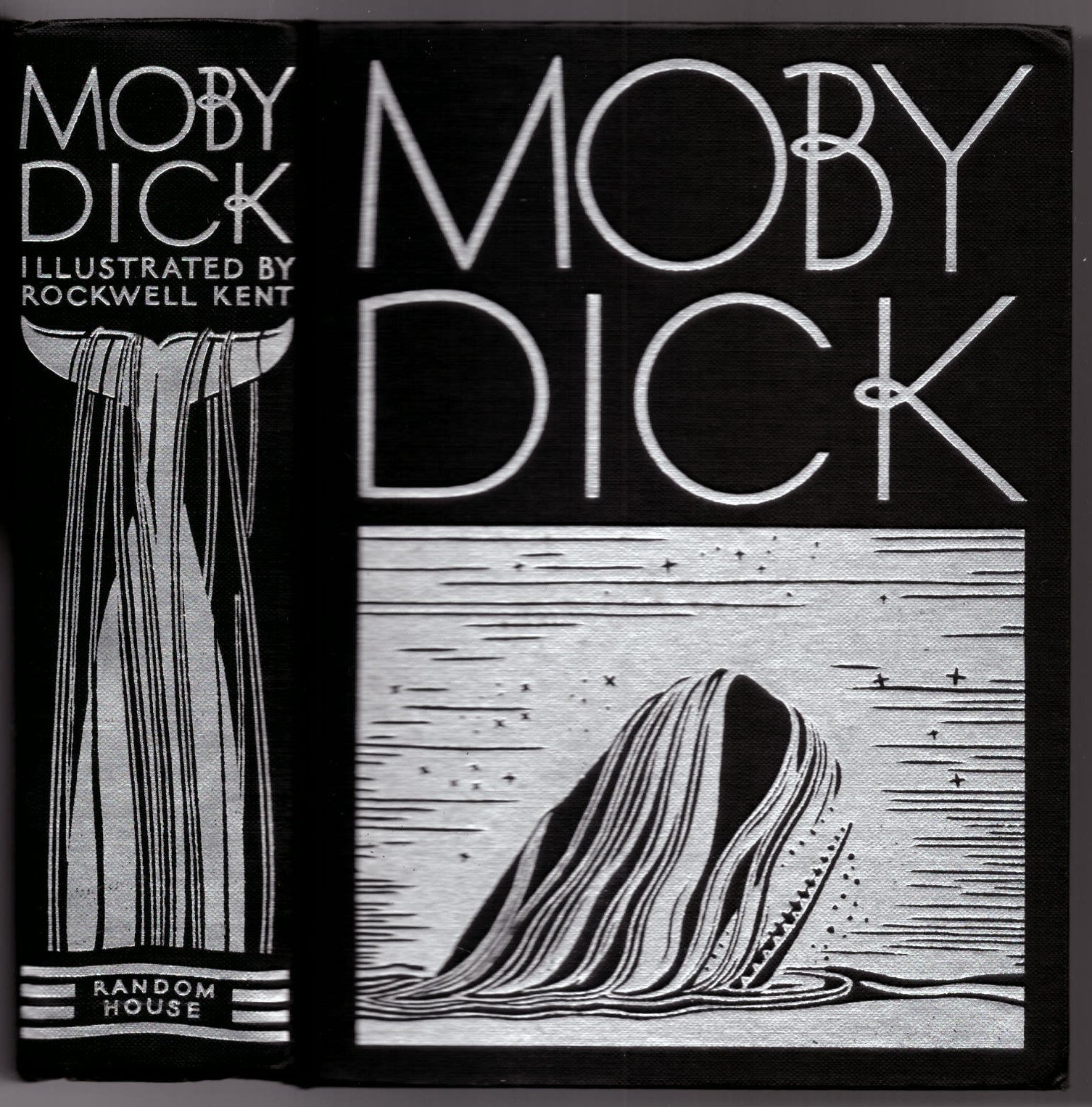

The 1930 edition of Moby Dick has marvelous illustrations by Rockwell Kent. In Melville’s lifetime, Moby Dick was not a financial success and was under-appreciated, selling 3700 copies over 4 decades. It was this 1930 edition with Rockwell Kent’s illustrations (based on his ink and wash drawings resembling woodblock prints) that caused Moby Dick to become regarded as one of the great American novels.

Greg recommended a natural follow-up to Moby Dick, the detailed, well researched and told In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, by Nathaniel Philbrick. A sperm whale dominated book cover on Facebook, posted by our divemaster Bob from last year’s Baja dive trip, led me to a follow-up fantasy tale utilizing quite a bit of sperm whale science in (mostly) creditable ways, Whalefall by Daniel Kraus.

The premise on which Whalefall is based is far-fetched, but the underpinnings of the story seem to rest on a real understanding of sperm whale biology. The whaling industry and its impact on whale populations figures prominently as a case study of man’s insatiable drive to plunder the ocean’s resources in my follow-up read: The Unnatural History of the Sea. I listened to an Audible recording, read by the author Callum Roberts. This was recommended to us by Alex (Mustard) during our blackwater workshop in the Philippines in November. Roberts details the long and sordid history of fishing through the centuries and the abundant evidence of sequential fishery collapses, with commercial industries responding by going further and further afield with more powerful vessels and efficient trawling methods, depleting one species after another. Data from commercial catches from the early 1900s until the 1980s shows indirect evidence of the impact of whaling, with sperm whales captured in 1905 nearly 12 feet longer in length than those measured in 1985. Today, adult female sperm whales can measure up to nearly 40 feet in length, while males range up to 60 feet. Calves measure about 13 feet in length at birth.

Seeing their tender interactions first hand makes the wholesale slaughter of these animals for centuries all the more horrifying. Their numbers have rebounded to perhaps 300,000 since the international moratorium on whaling took effect in 1982. I was startled to learn that sperm whale oil was in use as recently as 1971 as automatic transmission fluid in most American cars! Science has advanced our understanding of their familial and societal structures, with unique sequences of clicks called codas distinguishing groups of 20,000 or so sperm whales from others. Project CETI (Cetacean Translation Initiative) aims to take these discoveries to the next level, using AI to better decipher sperm whale clicks and codas, trying to parse out the ultimate in inter-species communication: just what are they saying to each other? The more I have learned about these cetaceans and their amazing capabilities, the more I too can’t wait to find out just what those clicks and codas signify.

A trio of sperm whales in Dominica takes off, bringing this whale tale to an end, a farewell for now.

-Marie

PS: February 22, 2023

As a fitting coda to our careers as radiologists at Scripps, after our last official day of work, we finally were able to see Patrick and the Whale, after Cindi texted us earlier in the day that she found it on PBS. It was a great way to relive the moving interactions of the whales we encountered and we both were completely in sync with Patrick’s sperm whale obsession.

PSS: March 5, 2024

Steve surprised me with an array of awesome birthday gifts! Besides some wonderful ikebana containers, both new and vintage, he also procured the 1930 Rockwell Kent illustrated Moby Dick I’ve been coveting.

this article is very useful, thank you for making a good article

How does the whale-watching season in January 2024 compare to other months in Dominica?

I don’t know, as that was our first trip there.