Our travels through the Côte d’Azur have been highlighted by sparkling artistic adventures, sometimes tracing the path of an artist we already admire, sometimes new discoveries. Our interest in contemporary and modern architecture led us to follow the trail of Le Corbusier, first in Paris and later, in the south of France. Yes, we travel for architecture. Also, art, food and views, but best of all, a destination combining all of these interests: oh la la, the Riviera!

Le Corbusier (né Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris) is an architect whose name is inextricably linked with modernity and the International Style architecture of the 20th century. Before there were starchitects, he was Europe’s first, complete with the distinctive glasses .

Steve channeling Le Corbusier atop Unité d’Habitation in Marseille (bust of Le Corbusier by French artist Xavier Veilhan).

Born in Switzerland, he became a French citizen in 1930. His initial training was in enameling and engraving of watch faces, like his father. A teacher who Le Corbusier later characterized as his “only” teacher, L’Eplattenier, introduced him to art history, drawing, and architecture. Initially intending to be a painter, Le Corbusier sketched and painted throughout his architectural career, as well as exhibited. With the Cubist painter Amédée Ozenfant, who he met in 1918, he founded a post-Cubistic artistic movement they called purism. With the poet Paul Dermée, the trio established the purist journal L’Esprit Nouveau (The New Spirit), an avant-garde puplication, in which they rejected decorative, non-functional architectural and artistic movements of the past. In the first issue, published in 1920, Le Corbusier adopted his new moniker, a variant of his grandfather’s name. Collected writings from the journal formed his seminal 1923 book, Vers une Architecture (Toward a New Architecture), in which the famous characterization of a house as a “machine for living” appears. In his 20s, he traveled throughout Europe, and apprenticed with several architects, notably Auguste Perret, a pioneer of reinforced concrete construction, a technique of which Le Corbusier was to make extensive use in his designs. His observations of monks living in beauty and peace at the Charterhouse of the Valley of Ema (in Tuscany, near Florence) reportedly influenced his developing architectural philosophy, setting the stage for later projects designed for groups of people living together.

Our first brush with this influential figure was in and around Paris, where he established his career and lived his adult life. Even before visiting Fondation Le Corbusier in Paris, we made a day trip in 2009 (probably our first RER excursion) to the town of Poissy to visit Villa Savoye, regarded by many as the seminal work of Le Courbusier’s career. (Reflecting our hard core Modernist tendencies, this was years before we finally made the day trip to Versailles!) The house was designed by Corbu with his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, and built of reinforced concrete between 1928-1931. It exemplifies perfectly his Five Points of a new architecture. Steve Rose, in an article in The Guardian from 2008, explains these concepts well:

“First, Le Corbusier lifted the bulk of the structure off the ground, supporting it by pilotis, reinforced concrete stilts. These pilotis, in providing the structural support for the house, allowed him to elucidate his next two points: a free facade, meaning non-supporting walls that could be designed as the architect wished, and an open floor plan, meaning that the floor space was free to be configured into rooms without concern for supporting walls. The second floor of the Villa Savoye includes long strips of ribbon windows that allow unencumbered views of the large surrounding yard, and which constitute the fourth point of his system. The fifth point was the roof garden to compensate for the green area consumed by the building and replacing it on the roof. A ramp rising from ground level to the third-floor roof terrace allows for an architectural promenade through the structure. The white tubular railing recalls the industrial “ocean-liner” aesthetic that Le Corbusier much admired. As if to put an exclamation mark after Le Corbusier’s homage to modern industry, the driveway around the ground floor, with its semicircular path, measures the exact turning radius of a 1927 Citroën automobile.”

Villa Savoye: Pilotis (structural columns) elevate the main living spaces to the second floor, leaving space underneath for a car to turn around. Horizontal bands of windows frame the views.

The ground-level structural columns, or pilotis, result in the living spaces and views being elevated.  As one moves around the open plan living spaces, the horizontal windows present a panoramic slice of the surrounding park.

As one moves around the open plan living spaces, the horizontal windows present a panoramic slice of the surrounding park.

The transitions between spaces are processional as well, with ramps leading from the interior to the roof garden.

The house very much engages with its landscape, with which it contrasts brilliantly. These concepts are so familiar today they don’t seem very radical, but when Villa Savoye was built in the late 1920s, this was shockingly different. That this seems SO familiar is a testiment to how influential is the legacy of Le Courbusier’s work and writings.

The house, like many architectural landmarks, had a checkered history. As owners of a white, contemporary house with ship-like railings and extensive walls of glass, we found amusing the correspondence inside the house between owners and architect, indicating there were ongoing construction issues and leaks which besieged the owners of the house, a wealthy Parisian family who commissioned it as a weekend house. Used by the family during the 1930s, it was occupied first by the Nazis during WW II, and later by the Americans. It had fallen into a severe state of neglect by the 1950s and faced demolition and appropriation by the township for use by the nearby school. It became property of the French state in 1958. A world-wide outcry by architects, as well as Le Corbusier, helped save the house from demolition. It was designated a French historical monument in 1965, the first modernist building to be so designated (notable also for occurring during Le Corbusier’s lifetime). After years of shoring up and renovation, from 1985 to 1997, it was opened to the public.

Years later, in 2011, we served as eager guinea pigs for my friend Margie’s ambitious architectural walking tour, which she was refining for her Paris Your Way clients, her individualized Paris itinerary service. Concentrated in the 16th arrondissement are a treasure trove of architectural gems, ranging from Art Nouveau (elaborate curvilinear forms adorning Hector Guimard designed buildings) to early Modernist designs of Robert Mallet-Stevens, and Le Corbusier.

Rue Mallet-Stevens in the 16th arrondissement of Paris was developed by and now preserves the work of the early modernist architect, Robert Mallet-Stevens

These two modernists anchor a corner of Paris. On rue Mallet-Stevens can be found his masterwork, built for twin brother sculptors Jan and Joël Martel. Just around the corner, off rue Doctor Blanche, is Fondation Le Corbusier, occupying Villa La Roche, aka Maison La Roche, designed by Le Corbusier and cousin Pierre Jeanneret in 1923–1925. It was designed for Raoul La Roche, a Swiss banker and collector of avant-garde art.

Steve inside the former Maison La Roche, now home to Fondation Le Corbusier, on a ramp which recalls ramps incorporated into Villa Savoye

In the summer of 2013, we finally found ourselves in Marseille, giving us the opportunity to see Le Corbusier’s signature apartment tower built of béton brut (rough concrete), which he called La Cité Radieuse (The Radiant City).

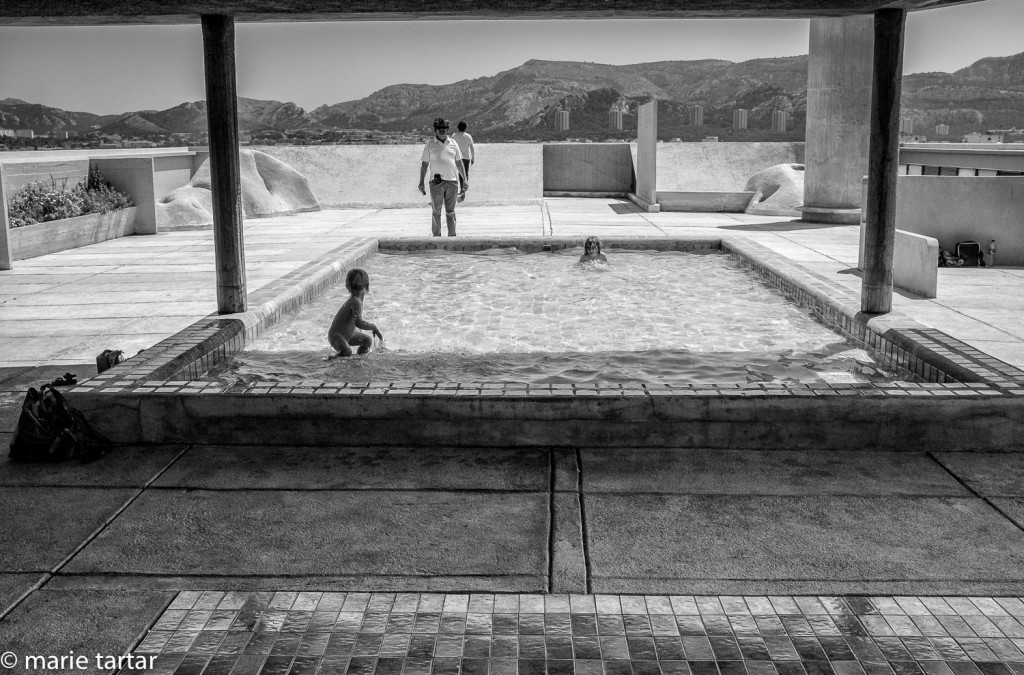

The destruction of WW II resulted in an urgent need for housing after the war. Le Corbusier’s response was his largest project to date. Built between 1946-52, it was envisioned by him as “un lieu de création artistique en plein ciel,” a place of artistic creation in the sky, with 337 apartments constituting “un village vertical, avec ses rues intérieures, son restaurant, son épicerie, sa librairie, son hôtel, sa crèche et son école,” a vertical village, with its own interior streets (corridors), restaurant, market, bookstore, hotel, nursery and school. Essentially, this was Le Corbusier’s model for an environment suited to modern life and he was to design Unité d’Habitation variations for other cities. His Five Points principles can be recognized. The 12 story structure is raised on giant pilotis, and encircled by a park. The roof terrace provides views, a children’s pool and a common meeting ground for residents.

The 337 apartments of varying size incorporate 2 story living rooms and are interlocking, such that the interior streets/corridors are only every 3rd floor.

Bright primary colors decorate exterior balconies and interior elevators at Marseille’s Unité d’Habitation

Our timing was inadvertently excellent for our first visit to Marseille, for in 2013, it was designated a Capitale Européenne de la Culture. For the occasion, many grand travaux, ambitious building projects, were completed. This also happened to be the same year a Parisian artist friend, Milène Guermont, was selected to embellish a hotel room in a small artist’s hotel, Au Vieux Panier, in Marseille. Strange how circumstances converge. Our being in the south of France that summer was prompted by a house exchange with a couple, Jacques and Veronique, with a traditional home in a small village called La Motte. Steve’s sister, Sarah, and her husband, Aaron, met us there, flying in and out of Marseille.

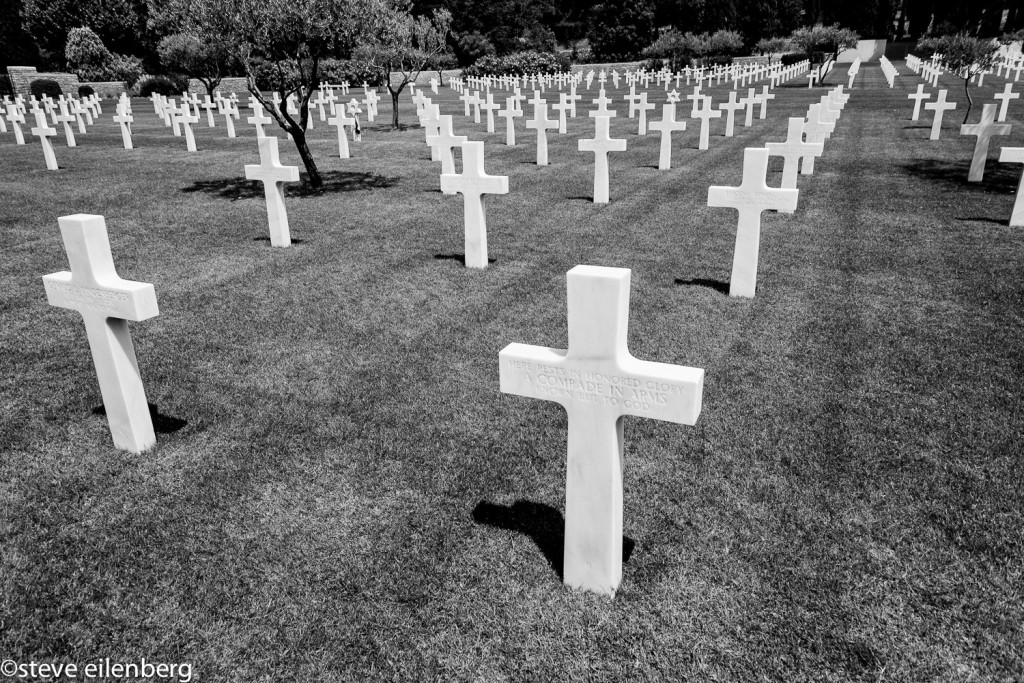

Just before our departure (Sarah and Aaron actually received their call while being driven to the airport by another sister, Susan), we learned their father, David, was dying of cancer. Relations with him had been estranged, essentially severed, since the difficult death of their mother, Mary, 5 months before, a trauma from which we were all still recovering, and one of the impetuses for this trip. Initially, it seemed David’s cancer was a recent diagnosis, and so, on the eve of our departure, I made arrangements to curtail our planned 2 week trip by a few days, and rerouted us to return via New York, stopping off on the East Coast before heading home. As it emerged over nightly I-pad and Skype mediated phone calls with Susan, we had been misled and the cancer diagnosis had been withheld for weeks, possibly months, and the end was much closer than initially presented. As it happened, David slipped away a few days into our trip. In France, it was July 4, 2013, and we thought of him as we visited a nearby American cemetery, a somber sight, with white crosses punctuating the landscape in numbers difficult to comprehend.

Marseille’s Unite d’Habitation remains in active use today. Most of the residents (per Wikipedia) are upper middle class professionals. The public can visit via several avenues. If not for our plans to stay in our friend Milène’s room at the artist hotel Au Vieux Panier, we might well have chosen to stay at the Hôtel Le Corbusier. We did have a wonderful gastronomic lunch at Le Ventre de l’Architecte. The decor is well preserved and our lunch was a pleasantly prolonged affair in the attractive dining room. At the time, the chef was Alexandre Mazzia and it lived up to a description I encountered before going of delivering “gastronomic treats to rival the sea views.”

Interior of Le Ventre de l’Architecte (Belly of the Architect) restaurant inside Marseille’s Unité d’Habitation

Also perfectly timed for our visit was the recent opening of MAMO, short for MArseille MOdulor, the refurbished rooftop solarium and gym of the building. French designer and Marseille native son Ito Morabito, known as Ora-Ito, acquired the rooftop in 2010 and transformed it into an art space, even realizing some architectural elements of Le Corbusier’s which had never been built.

Xavier Veilhan installation, featuring Le Corbusier himself, in a rooftop gallery in Marseille’s Unité d’Habitation

French artist Xavier Veilhan was the featured sculptor during our visit, the inaugural summer.

Sculptural installation on the rooftop of La Cité Radieuse by Xavier Veilhan, depicts Le Corbusier, Jeanneret et Buckminster Fuller, rowing

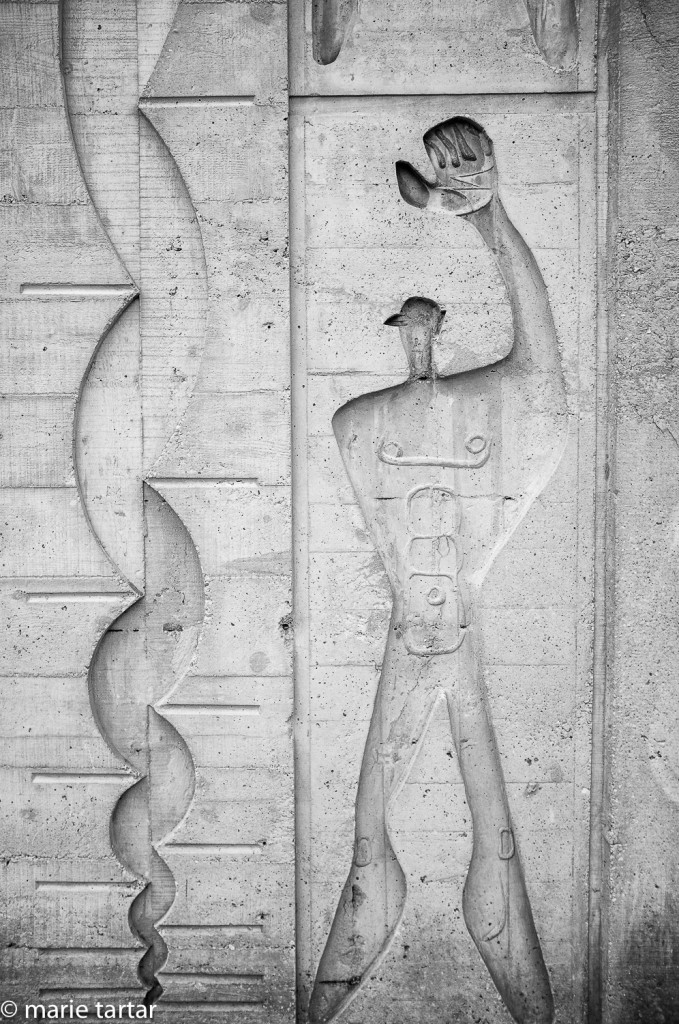

Another of Le Corbusier’s tenets is represented by the Modulor Man, who is omnipresent at La Cité Radieuse.

A man with a raised arm serves to underpin a system of proportions proposed by Le Corbusier as a unifying and harmonious scale of proportions for architectural use

The Modulor system was Le Corbusier’s attempt to grapple with the disconnect between the English and metric measurement systems (foot and inch vs. meters). He thought measurement systems should relate to the body, as the English system derives, and couldn’t relate to the meter being 1/40 millionth part of a meridian of the earth. His system, represented in the images by the swiggles adjacent to the figure, is related to the golden ratio, with a model human body’s height divided at the navel with the two sections in golden ratio, then those sections further subdivided in golden ratio at the knees and throat. This series of mathematical proportions derived from a human body could then be applied to architecture.

In addition to his design for La Cité Radieuse, Le Corbusier had another strong tie to the south of France. Beginning in the summer of 1952, he spent his summers in his version of a Cistercian cell for dreaming, his “cabanon,” a simple, one-roomed wooden cabin without a kitchen in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Reportedly designed in 45 minutes and built by traditional carpenters in the manner of a fisherman’s hut, it contained the bare necessities: a bed, a desk, a basin, bookshelves. “It measures 1.9 x 4 metres, it’s made of old planks put together, and it suits me just fine,” he said. Photographs show him living the Mediterranean dream, painting, eating at the adjoining l’Etoile de la Mer restaurant and working outside . He died there in 1965, apparently from a heart attack, while taking his morning swim, an event forecast by him in an interview with Brassaï in 1952.

“Je me trouve si bien dan mon cabanon que, sans doute, je terminerai ma vie ici.” (“I feel so well in my Cabanon that, without a doubt, I will end my life here.”)

Would that we all could end our lives just where and how we would want. Though not without controversy and detractors, Le Corbusier is no doubt a personnage of enormous influence on architectural and city planning thought, and tracing his footsteps has been a fascinating journey-hopefully, to be continued, eventually to see the Cabanon in person one day, the chapel of Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp…enough for one post! More on Marseille and the south of France coming…eventually.

-Marie

just wonderful to relive this trip, with its highs and lows.

Well done, Marie! It’s astonishing how crisp and luminous everything looks. I love especially your photos of Le Ventre de l’Architecte and of the Mallet-Stevens house on the Rue Mallet-Stevens.

Thanks Marie – everyone appreciates Le Corb differently, and seeing his works through your eyes is a lovely new coloration.