Five years had passed since my photography show at Jett Gallery (Robots Exposed), of x-rayed and CT scanned vintage toy robots.

Aside from my daily use of 3D work stations for clinical work as a radiologist, I had one non-medical 3D project in the ensuing years. I was fortunate enough to get my hands on CAT scan data of Peruvian mummies, all in death pose, some tightly bound in burlap and rope. These were scanned at our sister hospital, Scripps Memorial Hospital La Jolla for the Museum of Man, in San Diego’s Balboa Park .

With these experiences under my belt, a few years ago, I had contacted the Mingei International Museum (our world class folk art museum, also in Balboa Park) to see about gaining access to their collection of 50,000 plus items, looking for interesting objects to x-ray. I hoped these would be compelling artistically, as well as revealing in other ways (e.g. craft, construction, authenticity, repairs and hopefully, secrets).

Several months ago, I got a call from Mingei’s chief curator, Christine Knoke, with a specific x-ray project in mind. She explained that they were planning a show for 2015 highlighting hand made black dolls. Three stars of the show are black dolls created by Leo Moss, on loan from an East coast collector, Debbie Neff. Honestly, of the 50,000 items in the collection, I would not have gravitated to hand made dolls, but Christine’s background sketch and Debbie’s theories on the doll’s construction intrigued me.

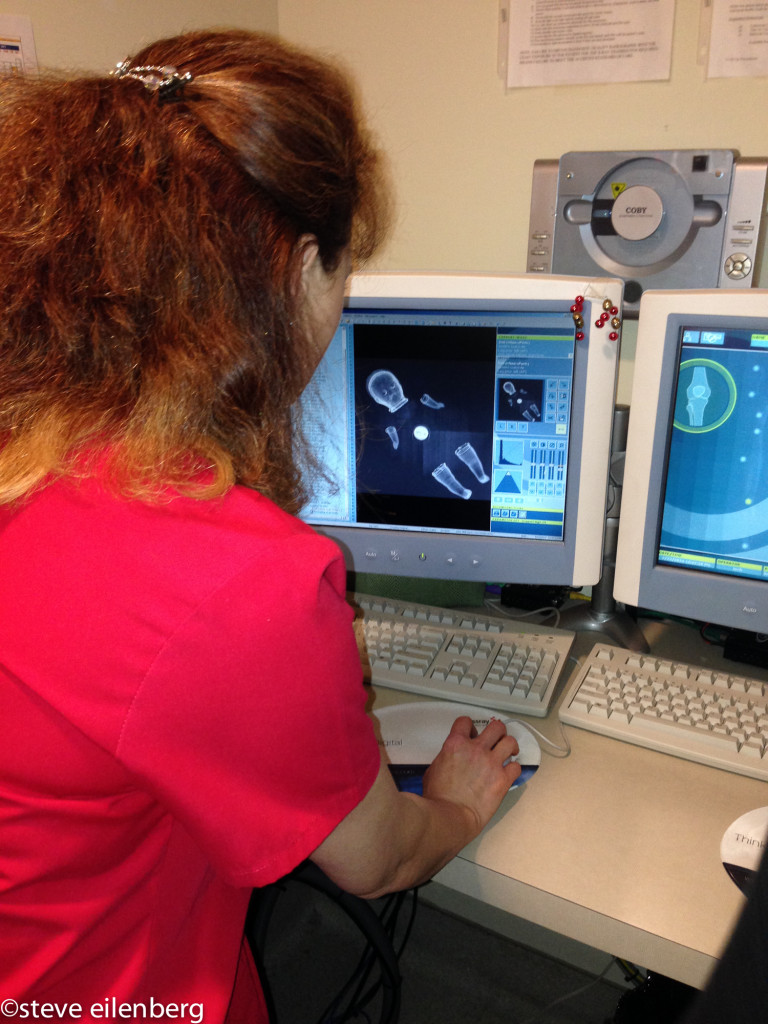

I approached Scripps Health with the project, knowing how important community outreach and support is to the organization. While not exactly on par with sending supplies and personnel to Haiti after the earthquake, I did feel the project had both artistic and social merit. Access was generously granted to our state of the art x-ray and CAT scan equipment.

X-ray imaging of non-biologicals is nothing new. Photographer/artist David Maisel has a body of work (History’s Shadow, 2010) centered around X-rays of museum statues and artifacts. These images were culled from museum conservation archives and reworked by the artist.

has a body of work (History’s Shadow, 2010) centered around X-rays of museum statues and artifacts. These images were culled from museum conservation archives and reworked by the artist.

In another instance, X-ray was used to image the interiors of “Nina and Lucy Ann”, two dolls held by the Museum of the Confederacy and thought to be smuggling dolls used during the Civil War. Quinine and morphine were hidden in the head and body, effective drugs to treat Confederate soldiers.

Morphine I understood, but it was news to me that in the day, malaria was rampant in the South.

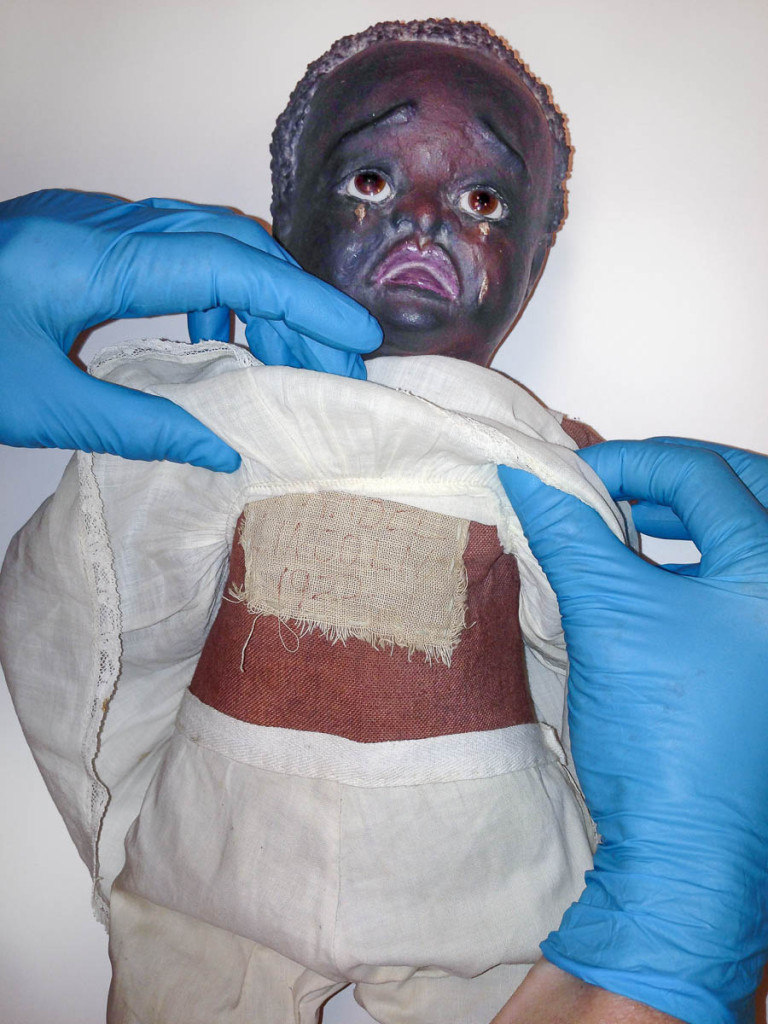

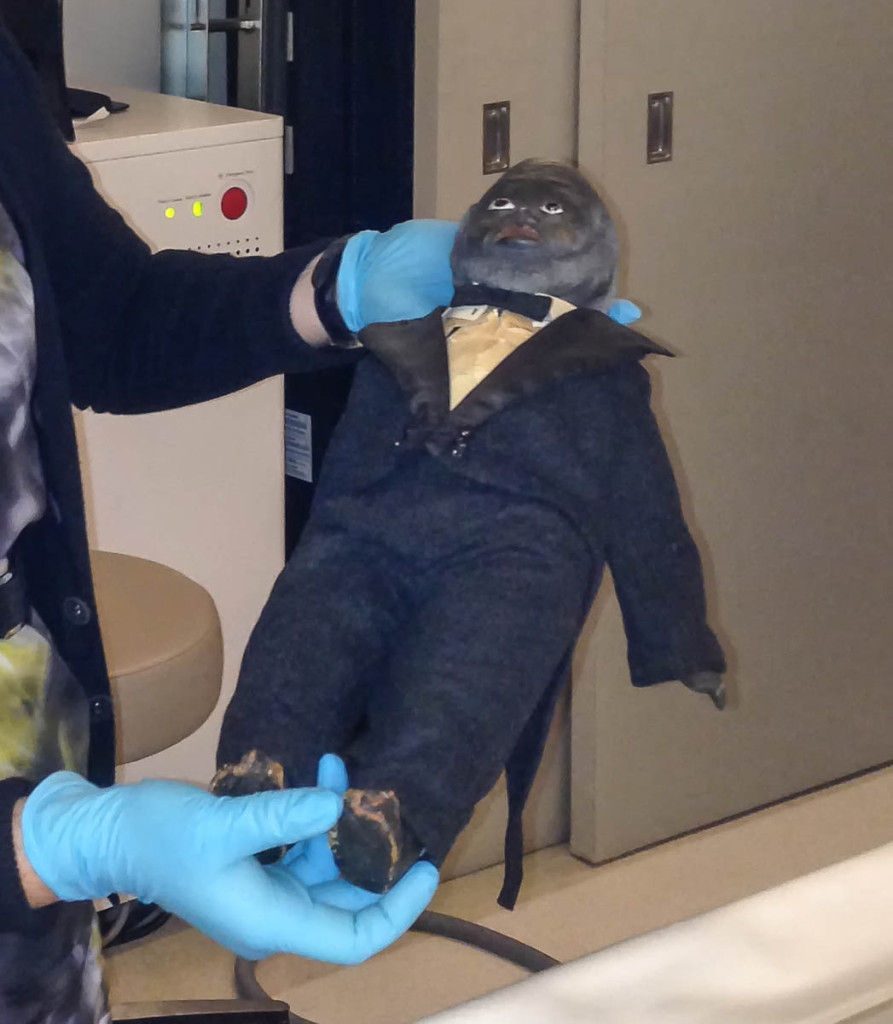

Debbie Neff’s dolls are quite fragile, but arrived in San Diego in better shape than many air travelers. The museum staff transported them to our imaging center and donning gloves, put the subjects on the examination table. Not knowing their composition, we had to make X-Ray adjustments on the fly to get the best possible images. Unlike our patients, we didn’t have to worry about the radiation dose in determining the perfect technique.

If you’ve read this far, you may be asking yourself “Who cares?”. The short answer is, a lot of people. There are doll museums, black doll authors and historians, a bevy of collectors, symposia, bloggers, and doll auctions. There is an E-Zine, a short documentary film and even a doll hospital staffed by Dr. Noreen, an in-house “plastic surgeon”. More importantly, it is about pride, identity, history and injustices.

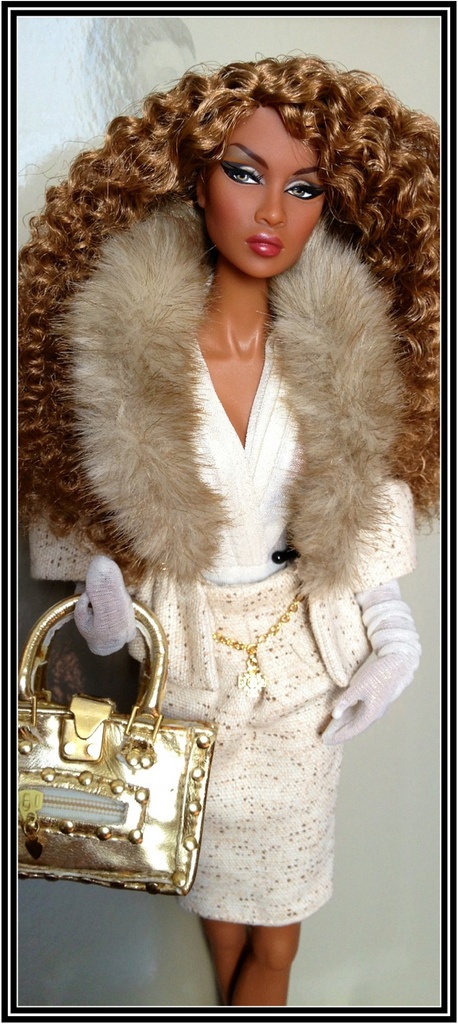

Shopping for a doll today is easy. All types are available, from glamorous to, well, you decide. Below is an example of a “fashion plate black doll” (maxed out credit card not included), followed by the epitome of self identification/self love (My Twinn) where a doll is custom made to look like its little owner.

There was time when black doll choices were slim. The high end options were European, expensive and made from white baby molds, dressed in white baby doll clothes. Below is an ultra low budget option; a home made black rag doll made from scratch. For just a little bit of change, one could buy a rag doll “kit”, printed on dark cloth. The cloth is cut and sewed, filled and dressed.

The most expensive option was to purchase a commercially available black doll, with black skin on white features and molded hair from a company such as Effanbee. The Effanbee name combines elements from the two principles, Fleischaker and Baum (F and B). They founded the company in 1912, but their business took off after German aggression made German made dolls in short supply.

This is Bernard Lipfert (1886-1974), a German doll sculptor, who designed the Patsy doll for the Effanbee Doll Company. After emigrating from Germany to New York City, Mr. Lipfert worked as a freelance sculptor, selling his work to many doll companies during his long career. In the above photo, he is shown sculpting in his home studio in Brooklyn. Highly prolific throughout his lifetime, Lipfert is responsible for most popular 20th century dolls, including Skippy, Toni, Shirley Temple, Betsy McCall, and dozens of other successful designs. This text is taken from “John Wright’s Made in Vermont” store

This Effanbee doll dates to the 1930s. It was fashioned from the white and very successful Patsy style doll. It is of composition material and the rigid body allows it to stand.

With this background in mind, enter Leo Moss. Below is from a wonderful blog written by Debbie Garrett.

“Leo Moss, a Black doll maker and Macon, Georgia native, made dolls in the late 1800s through the early 1900s. Friends and family are reported to have been the subjects for his dolls, many of which bore sad faces with actual teardrops molded into their papier-mâché faces. It has been written that the tears were added to Moss’s dolls after his wife ran away with the Caucasian toymaker from whom he purchased doll bodies. Another source indicates that when a child cried and could not be consoled while a doll in its likeness was being made, Mr. Moss added the tears. Leo Moss dolls are extremely rare and can sell for thousands at auction. (Excerpt from my book, Black Dolls a Comprehensive Guide to Celebrating, Collecting, and Experiencing the Passion, 2008).”

Garrett references an article by an owner of Moss dolls, Steva Roark Allgood, “To Leo Moss with love,” printed in the Fall 1987 issue of UFDC’s Doll News. “Leo Moss was a handyman by trade.” While most of his dolls were black, a few white dolls were made on commission. According to Allgood’s article, “Moss traded for chickens and vegetables to feed his family… The dolls were made from paper scraped from walls, boiled and made into a paste. Each head was molded individually and colored with a spray gun used for killing flies. Boot dye and stove blacking were used as the base color. The glass eyes were brown and inset into the heads. However, a few had painted eyes. Their hair was molded and their nostrils were usually pierced. Bodies were cloth with legs and arms mostly composition. The bodies were made by Lee Ann Moss, Leo’s wife, and some were from broken dolls they had been given… Another source of doll parts was from a toy supplier (a white man from New York) who sold seconds, or defective parts, to Moss. It is said that later this salesman ran off with Lee Ann taking the youngest child, Mina, with them. Henceforth, the dolls had tears on their faces, always appeared very sad and dejected, and reflected the unhappiness he felt over this tragic event.”

Best guess was that Leo Moss was a handyman/carpenter and part time doll maker. He and his wife produced one off black dolls for specific black girls. Some of the dolls had the owner’s name and presumably the completion date stitched to their chest. Were these gifts or commissions? OK, back to the X-Ray project.

Meet Crying Toddler, (AKA Violet Mae Collins 6-12-1933).

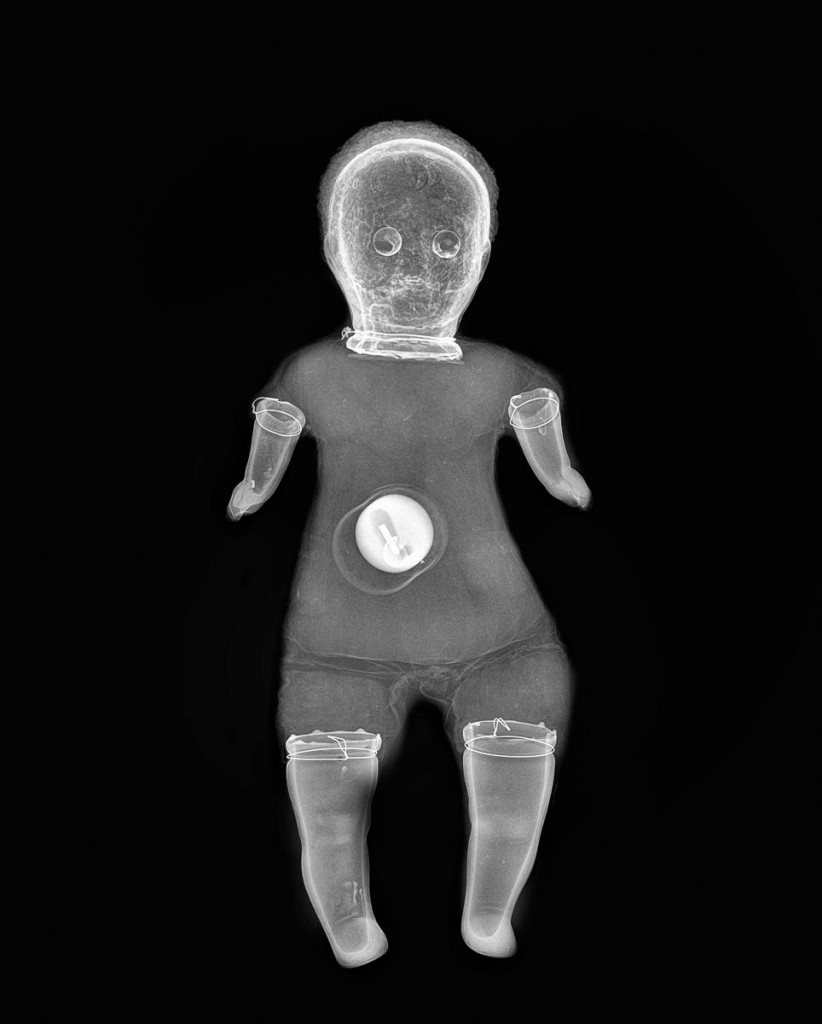

Arms and legs are composition (compo). This is a mixture of sawdust and glue. Limbs have been blackened. The x-ray sheds light on the internal structure. First, Leo Moss used an existing doll head and added/embellished with paper maché. He added nappy hair, altered the facial features, and added the tears. The doll eyes are probably exchanged, at least to a darker pair. The body is made up of two different stuffing materials and there is a now quiet voice box in the center of the chest. It probably made a “wah!” sound versus “mama”. Below the voice box are metallic pellets. Had the doll been used as target practice with a B-B gun?

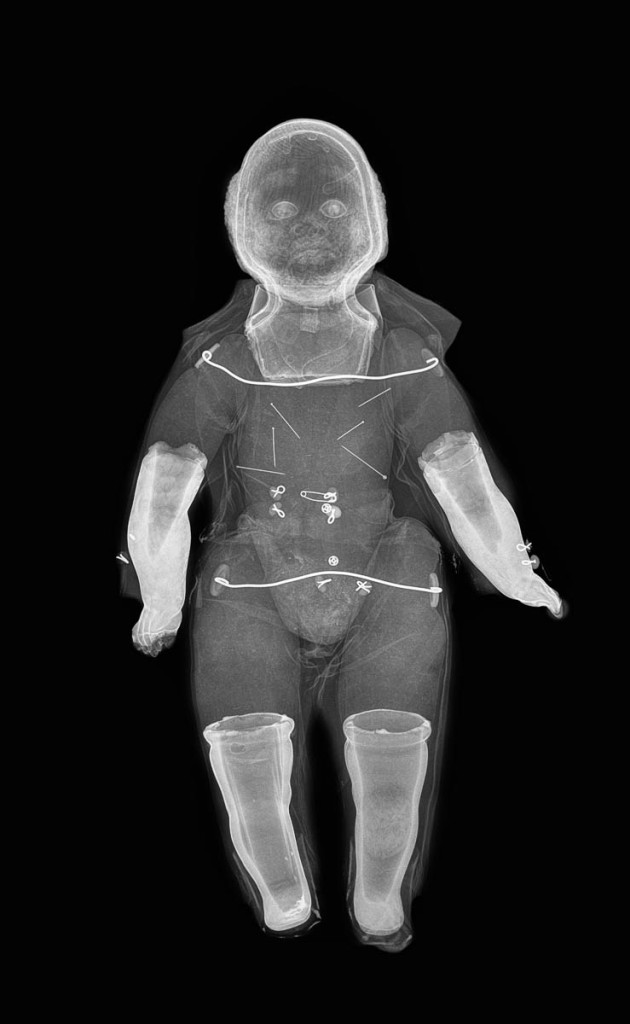

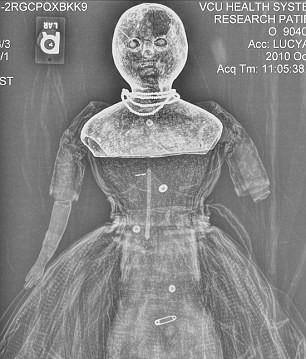

X-ray of the Crying Toddler. This doll was so long that the image is stitched together from 2 radiographs. Even with a regular x-ray, the crying face gives way to a smiling doll head which is under the doctored face.

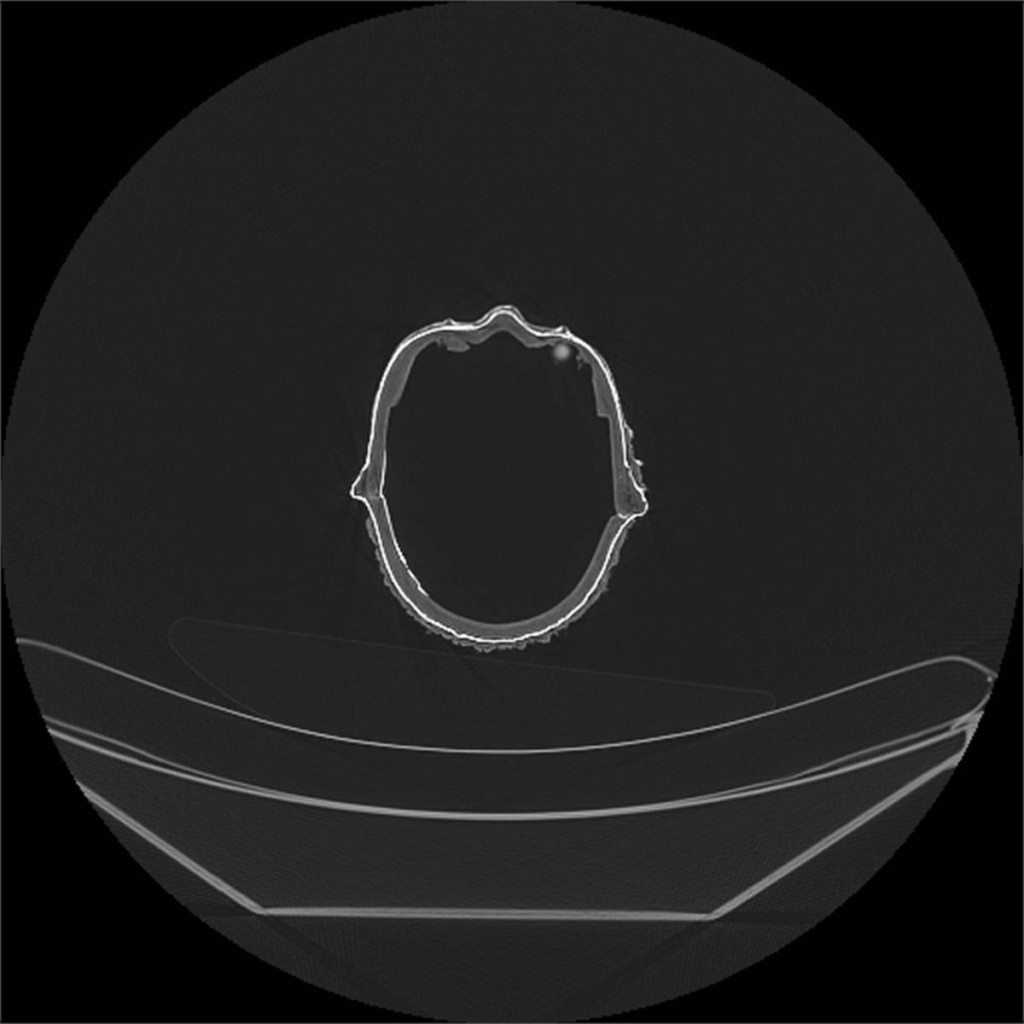

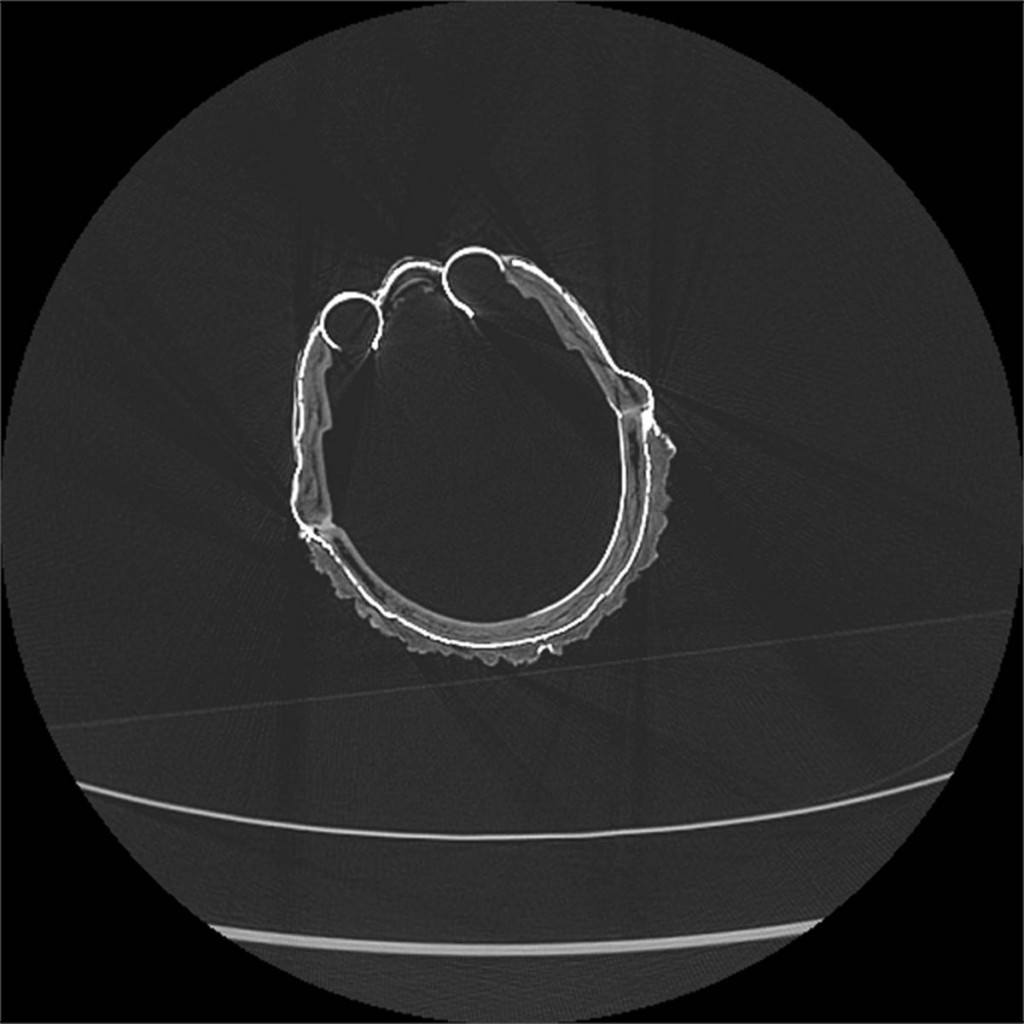

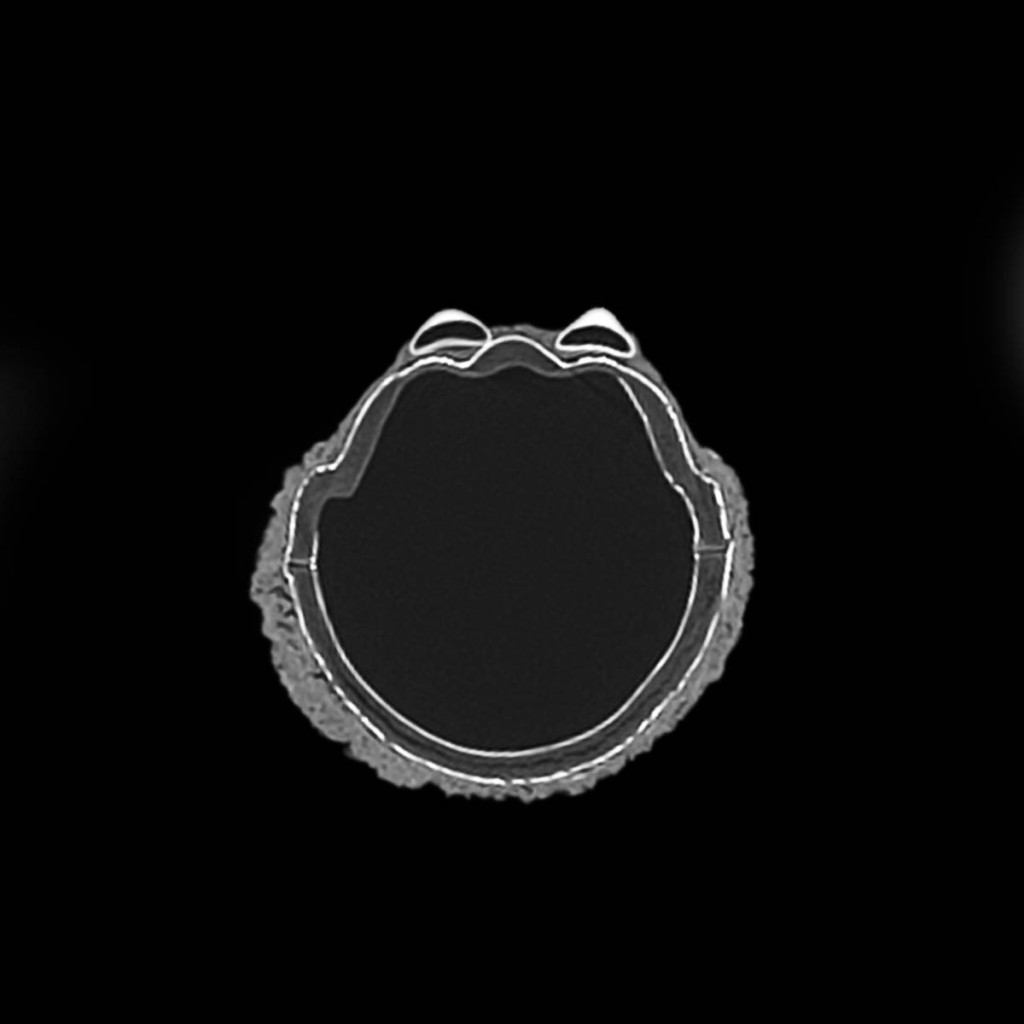

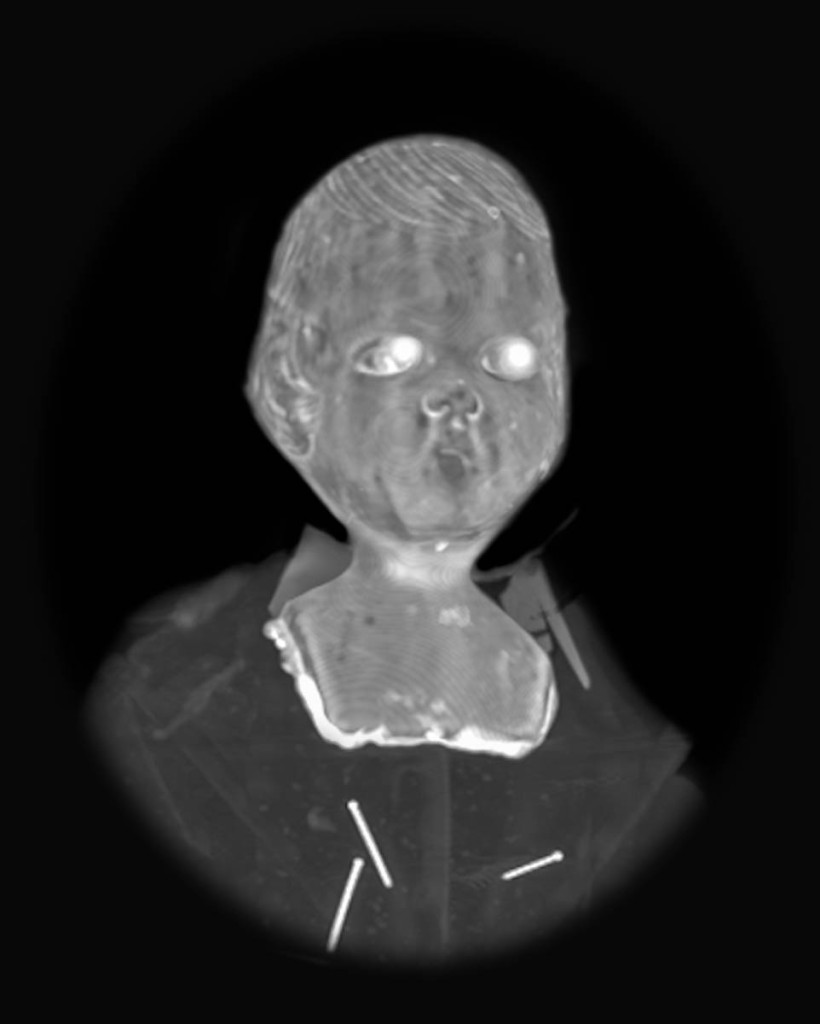

This is a single CAT scan slice through the head at the level of the nose and ears. There is just a peek view of the eyes. The outer material is paper maché and just deep to this is the composition head. The image is about .6mm thick. The CAT scan acquired many hundreds of images of this thickness from the top of the doll head to the bottom of the feet.

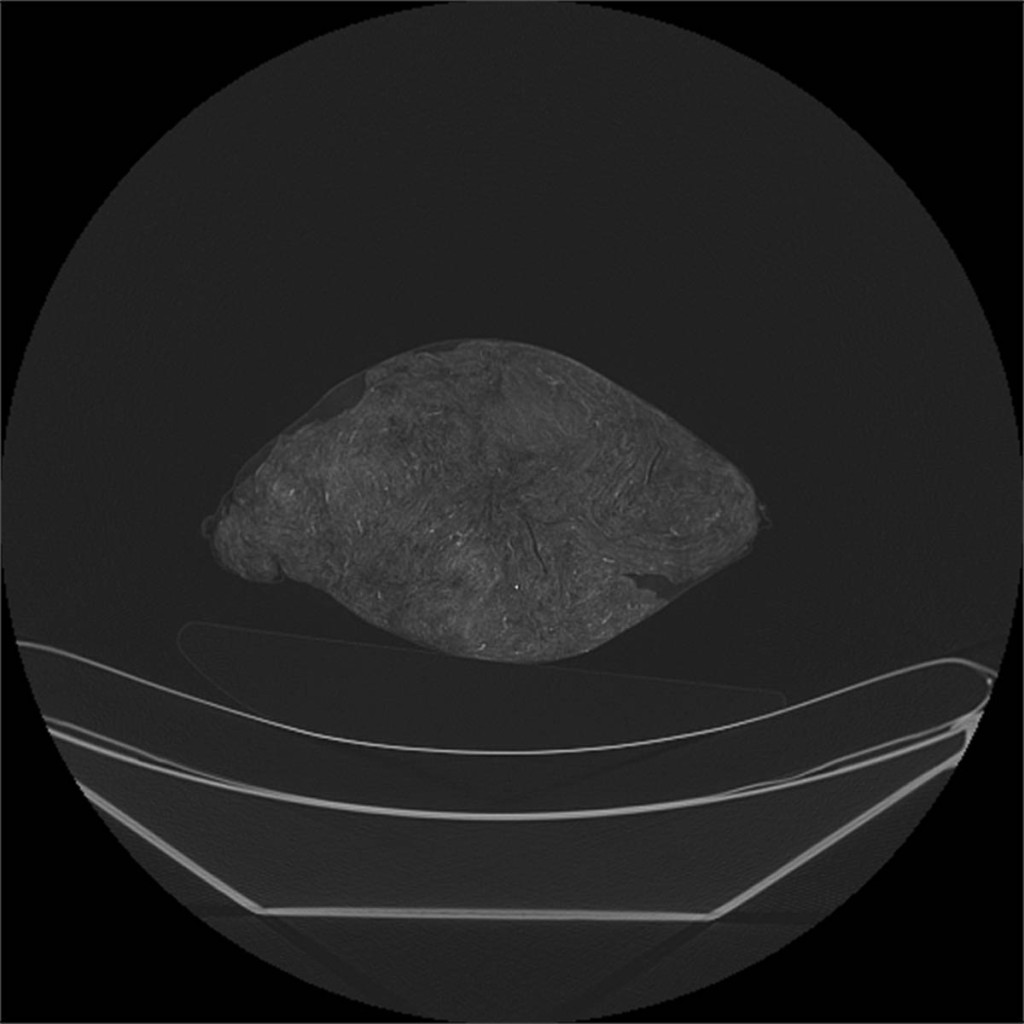

Halfway down the body is another cross sectional transverse CAT scan slice showing the stuffing material. The white dot may be a cotton seed. the banana shaped thing below is the pad on the CAT scan table

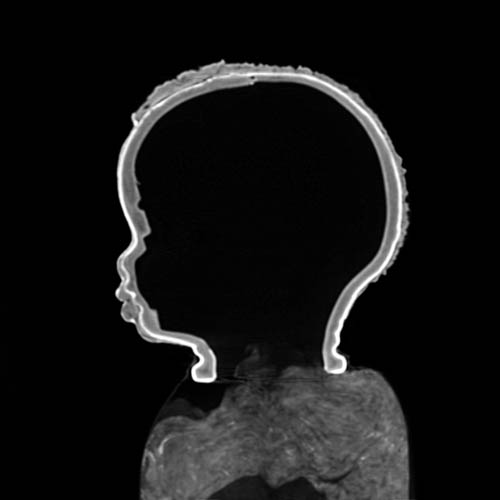

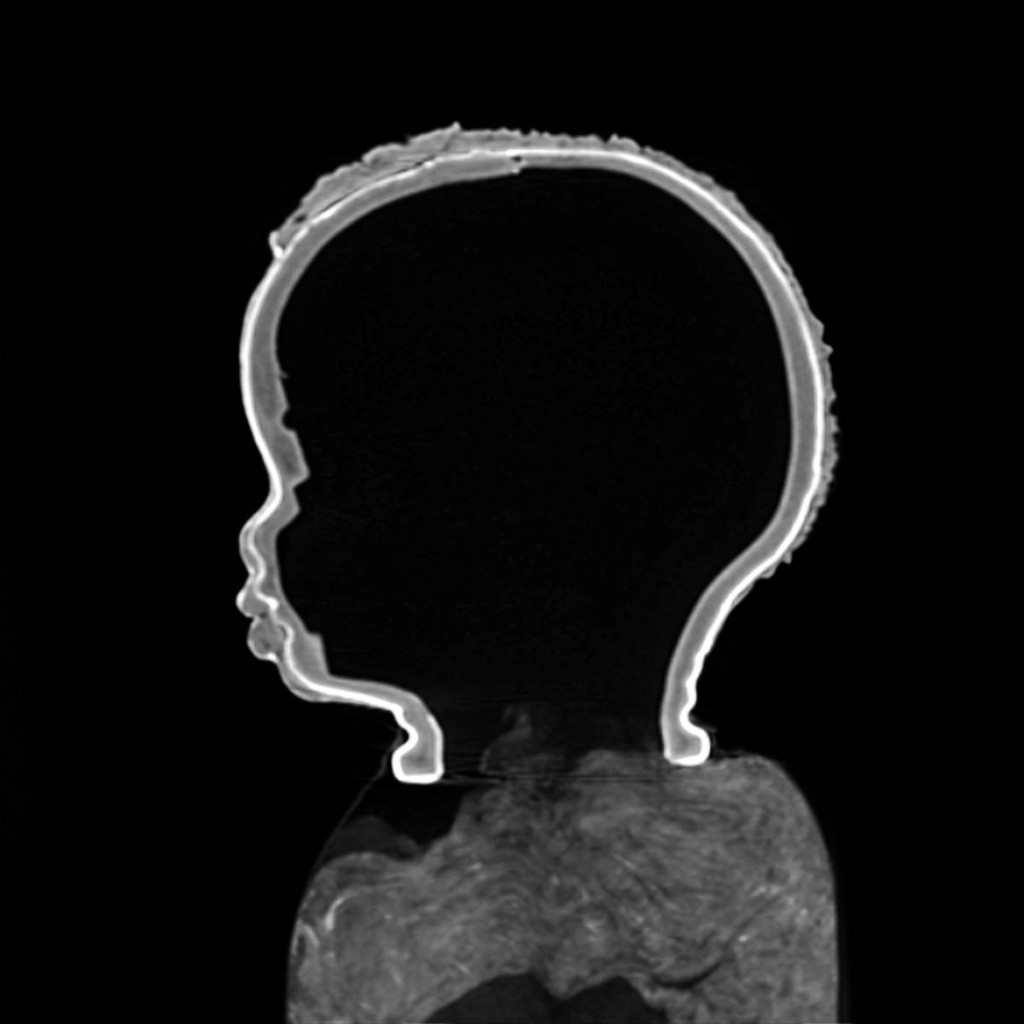

This is a reconstruction of Crying Toddler, in the mid sagittal (sideways) plane. It is computer generated utilizing hundreds of individual CT slices. Doll is “facing” to the left. One can see the added lips, broadened nose, and nappy hair, some of which is loose from the underlying compo head in the upper forehead region. This damage is not visible.

This is a coronal (frontal) multiplanar reconstruction of the CAT scan. We can now see that the original doll head had molded hair and there is a manufacturer’s name stamped on the back of the head and the head/neck junction. It reads Effanbee.

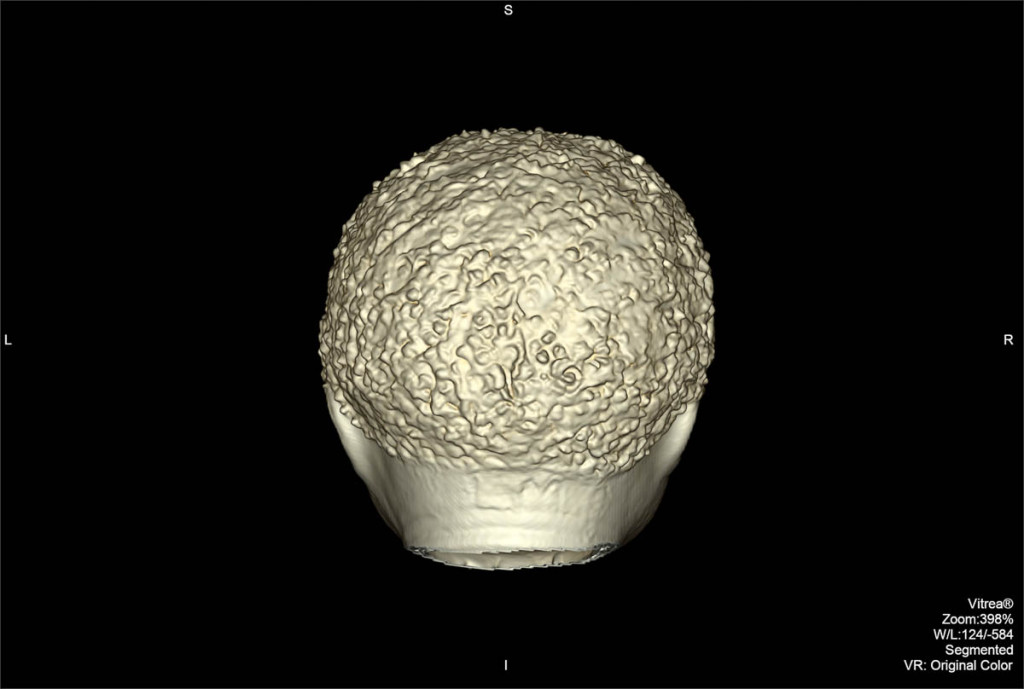

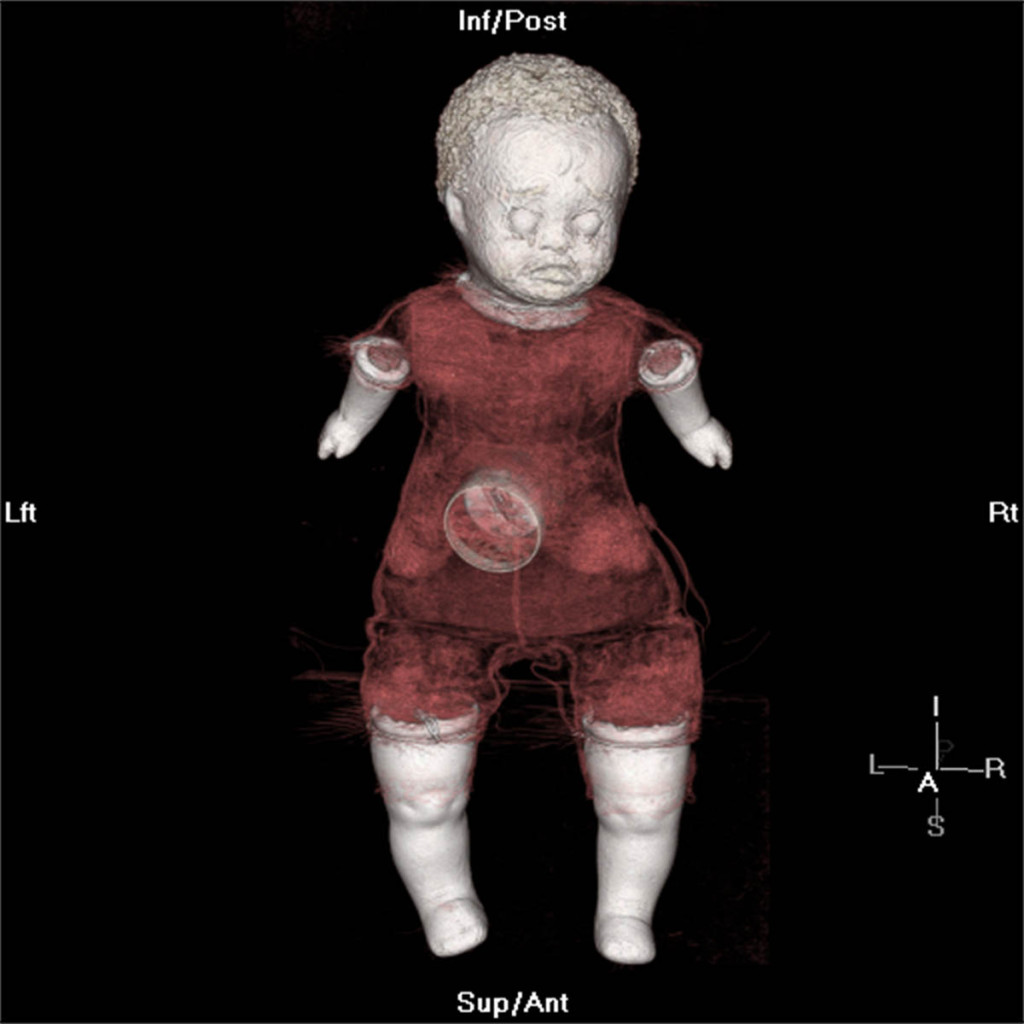

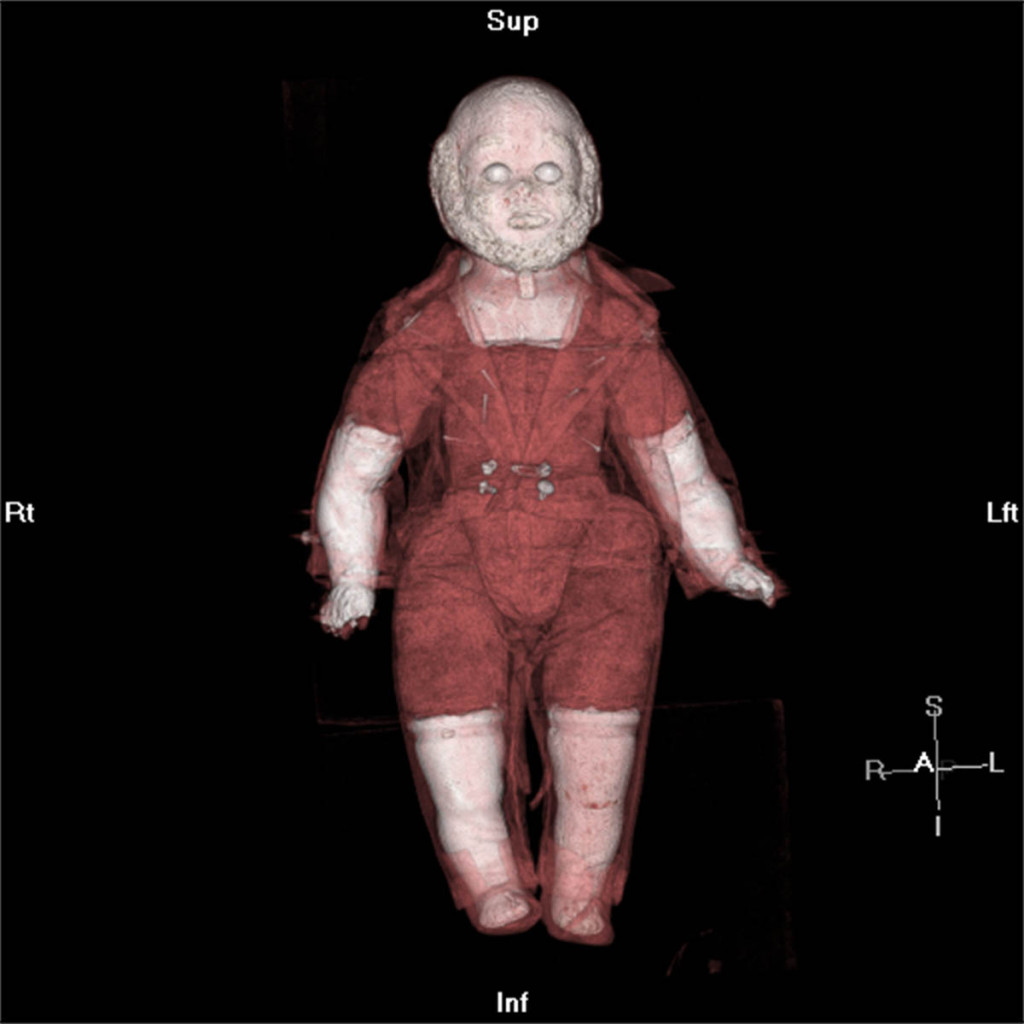

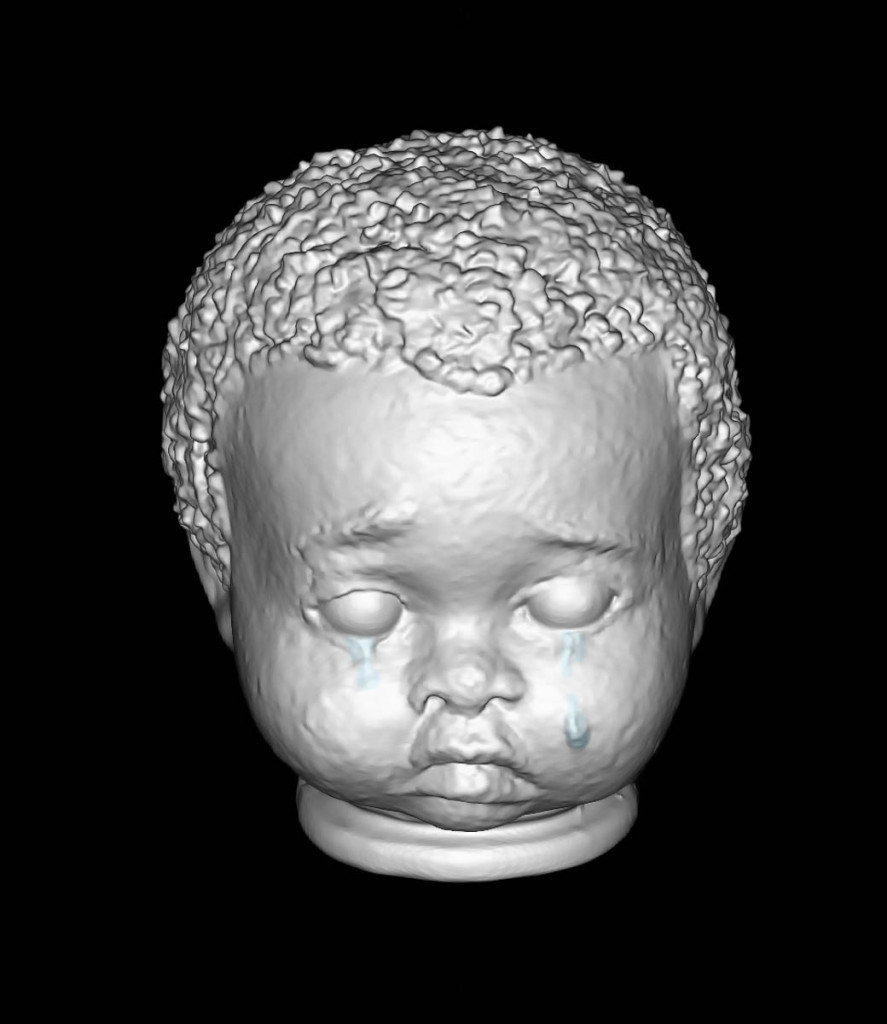

This is a 3-D surface display of the original CAT scan. It was created on a medical grade 3D work station used in clinical medicine. On the layer over the manufacturer’s name are carved the initials of Leo Moss (LM). This is just below the hair line.

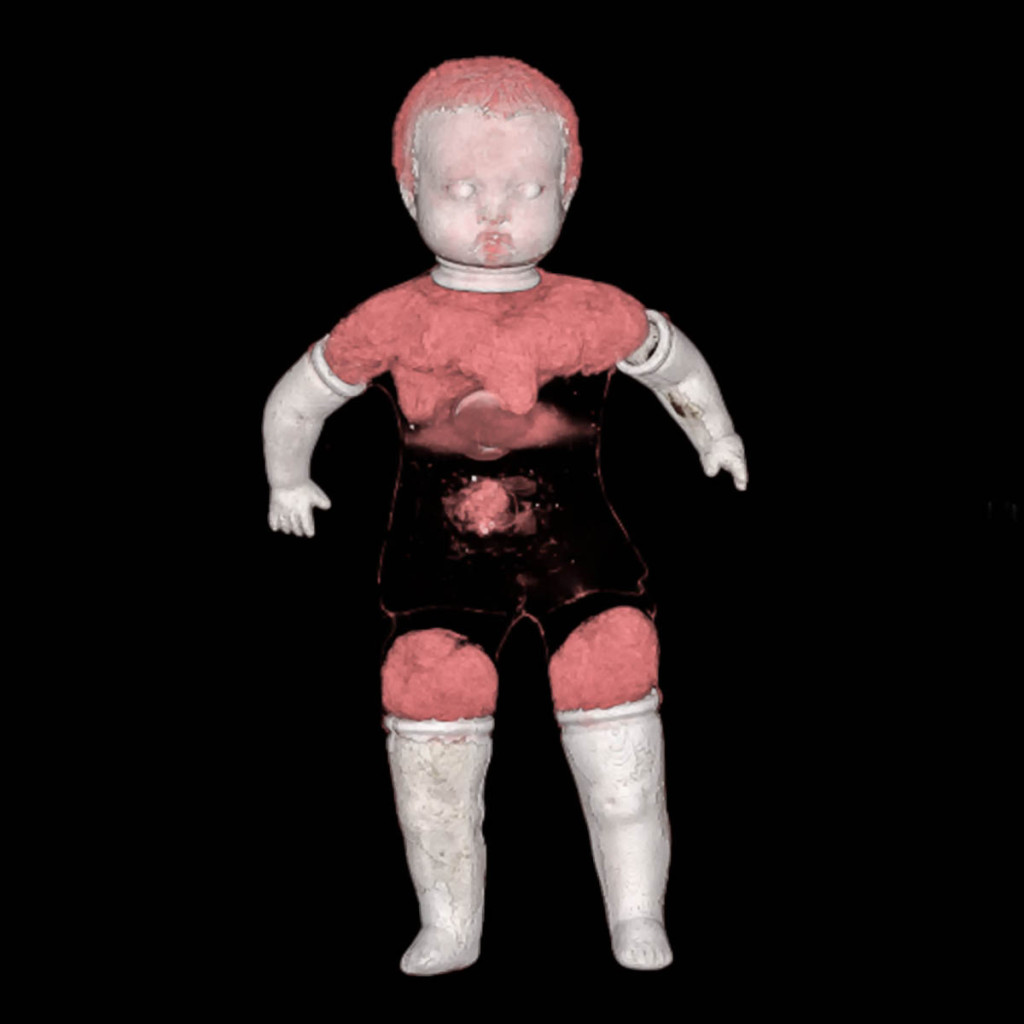

This is a 3D surface computer reconstruction of the CAT scan adding just a touch of transparency. Hair, fleshy cheeks, widened nose, large downturned lips and of course, the tears. One can now see the strings holding the arms on

This is a 3D surface computer reconstruction of the CAT scan adding just a touch of transparency and some obliquity. Hair, fleshy cheeks, widened nose, large downturned lips and of course, the tears. One can now see the strings holding the arms on

Final analysis: Built up composition head originally from Effanbee. Patsy style with molded hair. Original painted eyes removed and replaced. Two types of body stuffing. Painted or tinted composition arms and legs. Non functional voice box.

Meet Crying Baby (AKA Mabel Lincoln 1922). The doll is smaller than Crying Toddler, dressed and with a similar expression, tears and all.

Leo Moss handmade Crying Baby. The clothes were hand made by Leo’s wife. One gets a sense of mix and match doll parts, especially with the short arms.

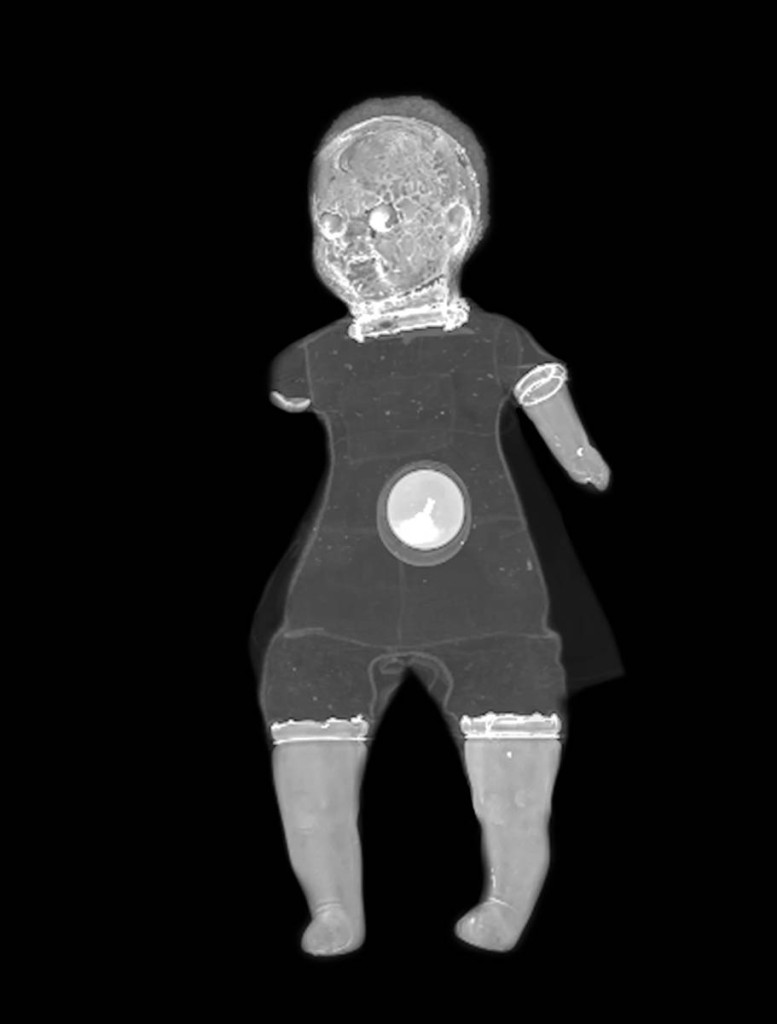

X-ray of the Crying Baby. It shows another happy doll head under the paper maché. A single stuffing was used on the body, and a voice box is seen (not previously known and not working).

This is a single .6mm slice from the CAT scan of Crying toddler. It is remarkably similar to Crying Baby with added eyes and paper maché embellishments to a composition commercially made doll head. Eyes have been added.

This image simulating an x-ray is made up of hundreds of CAT scan images. Using this computer generated imaging technique, I can subtract some of the doll tissue in front or behind what is seen as “an area of interest”, thereby gaining a clearer look at the original head (with molded hair on a composite construction) and a better view of the voice box. Note some debris in the stuffing; possibly cotton seeds.

A thinner section view of the entire doll made from the CAT Scan

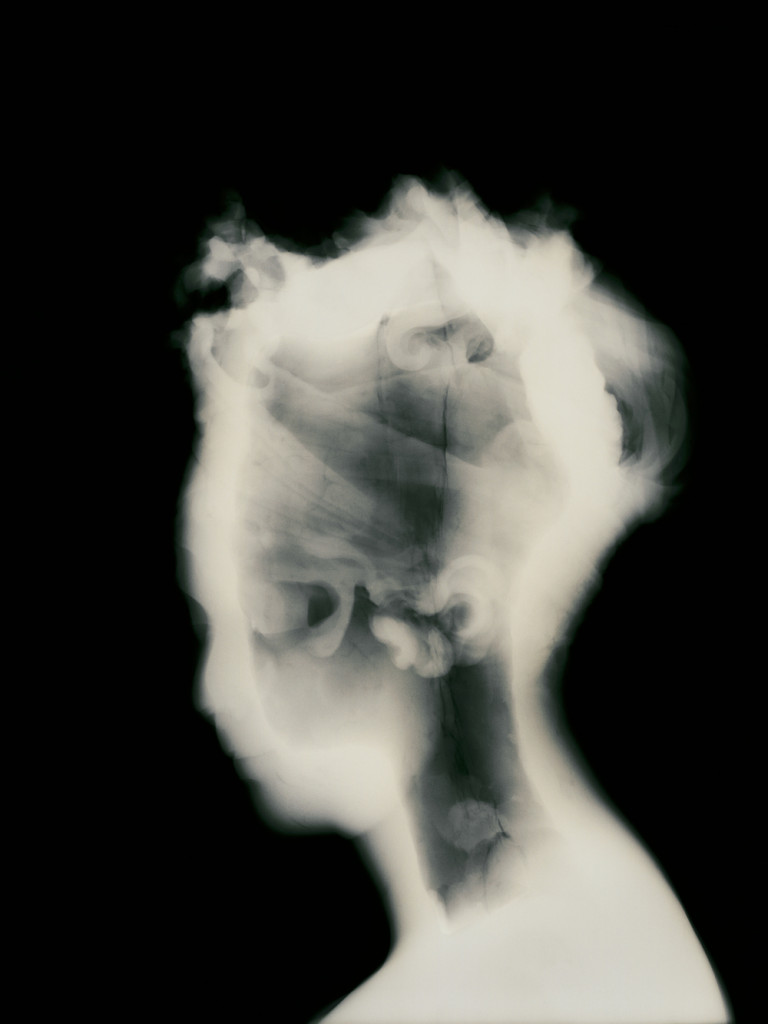

This is a semitransparent 3-D computer reconstruction of the Crying Baby showing different densities of the stuffing, perhaps the same material packed more densely in certain areas. The voice box is now quite clearly seen.

On this 3-D reconstruction, I’ve added enough transparency to see the voice box more clearly and the name patch, at the same time.

On this 3-D surface display, I have adjusted the transparency to remove the clothes (note hint of lace bloomers). This is very analogous to the body scanners used at airports today. If this doll was a screened passenger, it would be pulled out of the line to investigate the voice box.

Meet the “Man”, complete with nappy hair and beard, sporting a dapper outfit, including a stiff collar and bow tie. Unlike the other two dolls, he has a placid expression with no tears. Author and collector, Myla Perkins, speculates that Leo Moss may have made this in his own likeness.

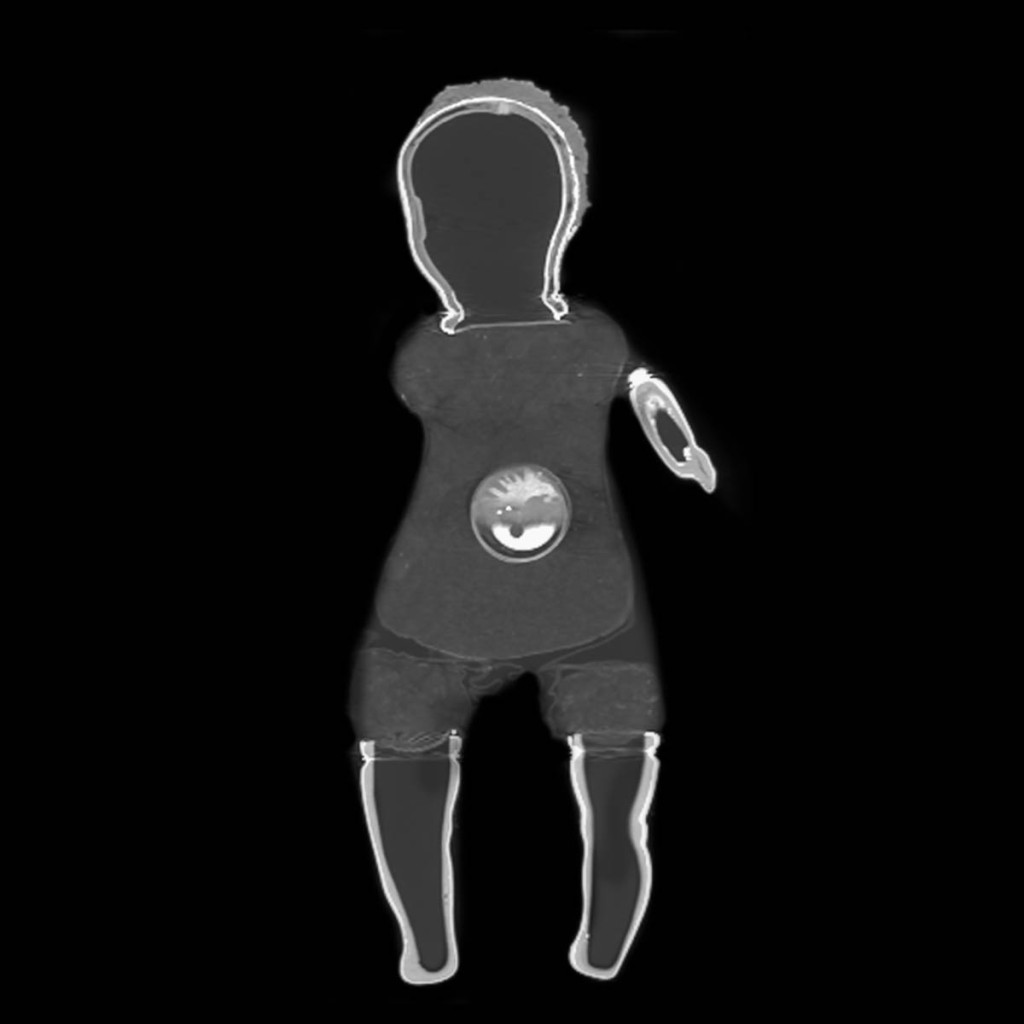

The Man seen here by x-ray. We see pins, needles and armatures. There is different stuffing in the crotch area and something has been added to the right leg. A voice box would not have been appropriate in this case.

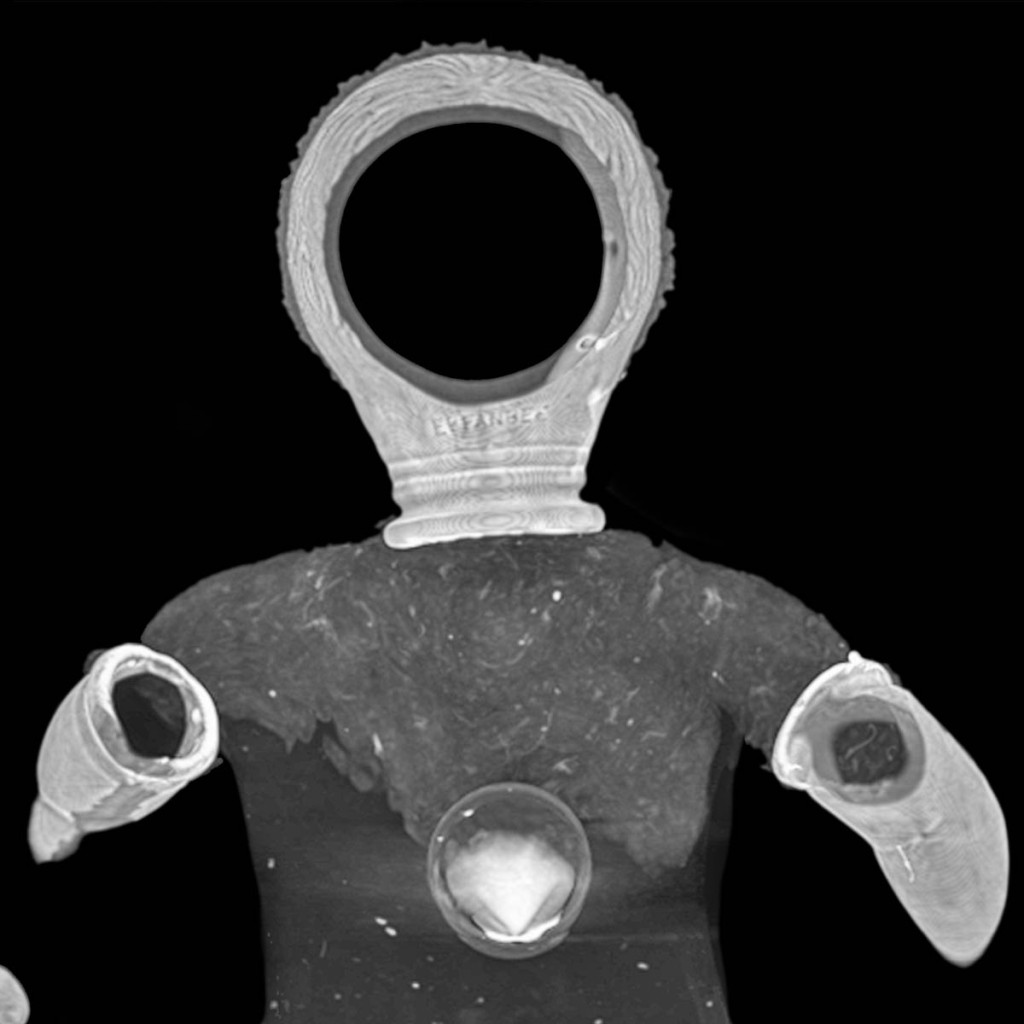

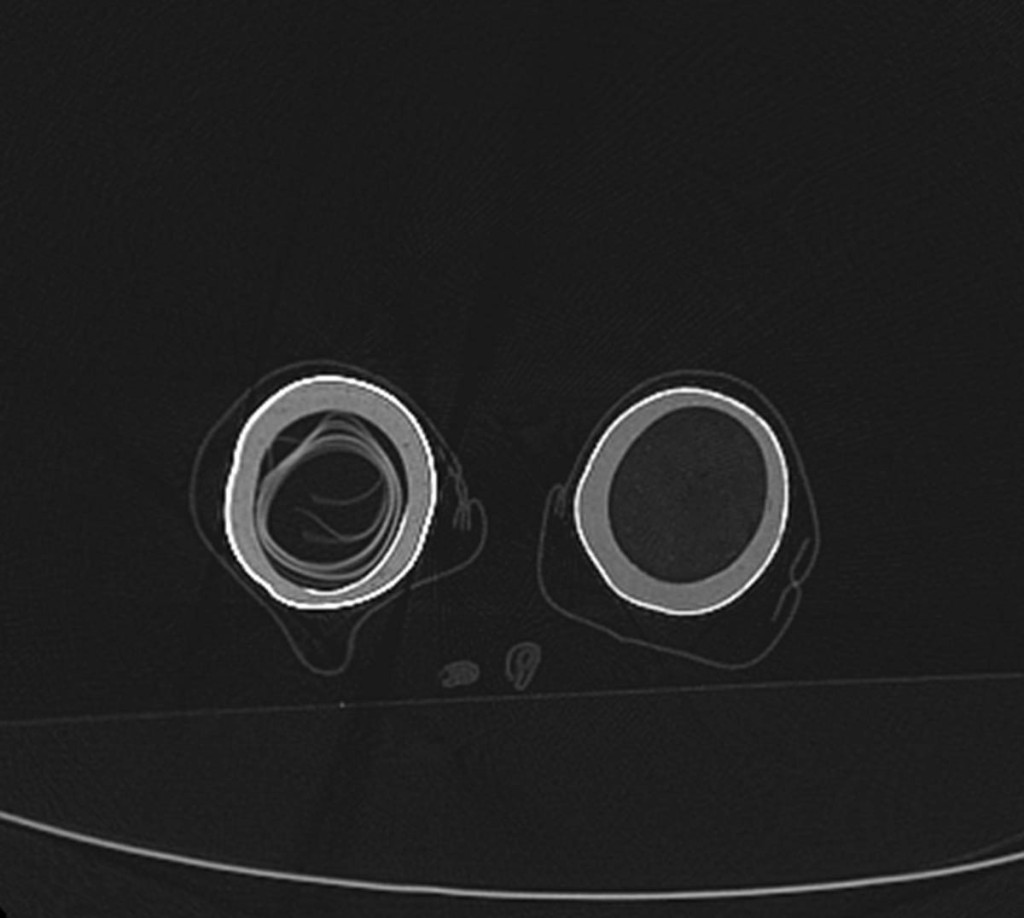

This is a transverse cross sectional slice of the Man’s head, at the level of the eyes. We see doll eyes added directly over the original painted eyes. As before, facial features are augmented with added paper maché.

This is a single .6mm transverse slice from the CAT Scan, through the composition legs. In the right leg (ton the left) are neatly rolled papers. This is unique to this doll. Is it simply a readily available stopper, holding back the stuffing or possibly a message or even a confession?

In this semi translucent 3-D CAT Scan reconstruction, we see both faces, and a different composition head than the other two dolls.

There are many ways to look at the doll’s components. Here, the 3-D computer work station was tasked to just show hard and dense things, like the pins, buttons, composition material and armatures.

On this thick slice coronal (frontal) 2-D computer reconstruction of the CAT Scan, we see a balled up rag holding back the stuffing from entering the left leg and the paper roll holding back stuffing on the right side.

This what the actual doll head looked like, under the paper maché. The added eyes, unlike the other two, are over the original painted eyes. The composition doll has molded hair and fine features of a boy, possibly European. The hard collar and pins are also well seen.

This project was a very enjoyable and interesting exploration for me. Like most topics, a scratch at the surface, can lead to a vast, rich, multi-layered story. The need filled by Leo Moss was a social imperative, created by societal and economic injustices. These dolls are part of his legacy and of our collective history. I am glad that Scripps Health and I were able to shed some light on this fascinating history. I look forward to the show at Mingei International Museum in 2015.

-Steve

Thank you for your research. The knowledge I gained will further support the message I try to convey in my Black Doll presentations. Mary Swift Little Rock

Thank you for your work and for this excellent article.

Is there anyone performing x-ray examination for authentication of Leo Moss dolls at the present time?