“If you like San Miguel de Allende, you should really visit Guanajuato.”

How many times did we hear this last year, on our first trip to Mexico City and San Miguel de Allende, from virtually every Mexican to whom we spoke ? Friends from San Diego, Randy and Stephanie, had been drawn there over and over again, including 4 months during Randy’s sabbatical, years before.

The name Guanajuato apparently is a Spanish approximation of Quanax-juato (Place of Frogs), as the indigenous people who preceeded the Spanish called the region. The Spanish were drawn by rich veins of silver in the surrounding mountains. Guanajuato’s physical situation is unique, in a valley surrounded by silver mine bearing hills, with a network of underground roads and tunnels.

These tunnels were originally constructed around the turn of the 20th century as a response to catastrophic floods resulting from the funneling of rainwater into the narrow valley in which the town is located. They were eventually widened and paved to accommodate car traffic, preserving the historic grand colonial buildings. The local expertise in silver mining, which led to the town’s establishment, growth and wealth centuries before, was put to use in construction of this network of underground tunnels, preserving the overlying historic town center.

Guanajuato’s colonial heritage, in the form of a series of charming and livable interconnected parks, plazas and squares in the Centro Historico, contributed to its designation as a World Heritage Site back in 1988.

The triangular Jardín de la Unión (hereafter el Jardín) is lined with coifed Indian laurel trees, and is a lively gathering spot for families and visitors alike.

Guanajuato’s Jardín de la Unión is a central gathering place for families, lovers and tourists alike

We always seem to have adventures (mostly minor) en route to new destinations. In the 24 years we’ve lived in San Diego, we had only made one trip out of Tijuana International Airport, one year ago, on Volaris to Mexico City. After comparing notes with our friends and fellow travelers on that trip, Gail and Ralph, (us: Coaster train from Solana beach to downtown, then Volaris shuttle bus to airport; them, professional chauffeur Howard driving them to Otay Mesa border crossing, walking across, and taxi the couple of miles to the airport), we decided to give the Howard express a try. At 9:45 in the evening, our journey started. Forty-five minutes and $80 later, we were walking across the border, where a quick $15 cab ride had us to the airport in under an hour total. The Volaris option was cheap ($20 per person) but definitely more time-consuming (requiring disembarking at the border and reboarding the bus).

It felt more than a little strange initially, walking across the border late on a Friday night on a dark road, but there were other pedestrians walking their suitcases. WHY the Volaris flight (the only non-stop option to Leon) leaves at 1 am, I have no idea.

Safely at the airport, we were determined not to make the mistake we made on our only prior Tijuana departure; namely, not getting a visa (good for 6 months) prior to checking in. This was the most time consuming aspect, with a line and forms to fill out. The fee (306 pesos, about $22) can be paid in dollars or pesos.

Our prior trip, we had packed expecting to carry on, but were forced to check, not having paid for the privilege in advance. This time, having reserved this option in advance, this was no problem. However, in security, my carbon fiber tripod invited scrutiny and I was told it wasn’t allowed, being “too long.”

OK, back out of security to the check in area I returned. The Volaris agent told me this wasn’t their policy or even a universal policy in Mexico, but unique to this airport. But, when I was disembarking, I saw another passenger carrying a long box containing a tripod off the plane, suggesting this perhaps wasn’t unique to the airport, but specific to the agent. Hhhmmph!

When we boarded, I was in front of Steve, arriving first at our adjacent aisle seats. To my horror, I saw that one half of one was fully occupied by an oversized man in the middle seat, seat belt expanded, extending well into the aisle seat. Telling Steve to take the other seat, I found a stewardess and told her, as quietly and discretely as I could in Spanish, that this was not going to work. Luckily for me, one of the few unoccupied seats was an aisle exit row seat a few rows up, so this potential disaster worked out fine. It was already going to be a sleepless night, boarding at 1 am, a 2.5 hour flight , and early morning arrival at 6 am, with a 2 hour time change. Bad enough, without adding a cricked body to the mix.

The cab ride from Leon takes about 25 minutes (470 pesos, about $30). Randy met us on the road down from the house, where the wayfinding became tricky. After breakfasting on homemade scones and coffee, Steve and I retired for a morning catch-up nap. Once revived, we had lunch on the patio with Randy’s scrumptious vegetable frittata and HOMEMADE English muffins, complete with interior nooks and crannies.

We shoved off after lunch, heading downhill to town, where we checked out small museums on the same street (surrealist Leonora Carrington at Museo de Arte Contemporaneo and Museo del Pueblo de Guanajuato), and oriented ourselves by walking past the Universidad, Plaza de la Paz and El Jardín.

It was Saturday night and the jardín was hopping.

Inside a courtyard, we attended a concert (9 guitarists, one cellist and one man holding a sign and singing) at Mesón de San Antonio, celebrating Santa Cecilia, “virgin, martyr and patroness of music”. The recent rain made the benches damp, leaving us with cool bottoms by the time we headed out to Le Midi for dinner. Even there, we had musical accompaniment, with an opera singer performing at a gallery in the building when we arrived, and estudiantina troubadours passing by on the street below, trailed by their followers.

Sunday, November 23, 2014

After a leisurely morning, we set off by cab to Marfil to the Gene Byron house museum for a concert. She was a Canadian artist who came to Mexico after being blacklisted during the McCarthy era, curtailing her successful broadcasting career in California. The concert, interpretations of Brazilian chorro music by a clarinetist and guitarist, was lovely, with a reception afterwards in the courtyard.

We tore ourselves away from the guacamole to head across the street to a carnitas shack Randy and Steph knew from their prior stay in this neighborhood.

The tortas were delicious and the proprietors welcoming.

We headed toward town via the old road, along the river, a pleasant shaded amble leading us to Museo Ex-hacienda San Gabriel de Barrera.

This hacienda was acquired by the family of Gabriel de la Barrera and inhabited by the captain, his wife, 2 daughters, a housekeeper and a priest.

Our tour guide, working for a tip which he well earned, kept us entertained with his descriptions of life in the 1700s. The older daughter shared a bath with her mother, and was allowed to marry, while her younger sister was expected not to marry in favor of caring for her parents in their old age (the central theme around which revolves the Laura Esquivel novel “Como Agua para Chocolate”). In this family, the younger sister apparently ran off with a staff member, leaving the older sister to call off plans for marriage to care for her father, her mother having been murdered by a jealous lover (one of a reported 24). At this time, a husband had to be granted permission by the priest to procreate with his wife, although permission wasn’t apparently necessary for the master of the house to sleep with a slave.

Interior, Ex-Hacienda San Gabriel de Barrera. Something about this seemed to spookily evoke the church’s power

The black slaves, working in the house, had longer life spans than the indigenous people employed outside, working in the mines. Lifespans also were short for the women, whose waists were constrained by corsets. Women’s breasts were on display in the dress of the day, but to show a glimpse of ankle was to risk being branded a prostitute. The wife of the house had no power, while the housekeeper, appointed by the King of Spain, ran the household and served to spy on the homeowner, ensuring the King received his cut of the mine’s profits (20%).

The ex-hacienda lay dormant for longer than a century before being acquired in the 1940s by a rich business man, who restored the property and furnished it with dispersed period furnishings. The property was wrested from him in the late 1970s by the Governor. In 1979, the State government took over the property when the governor was indicted-apparently the money he used to acquire the property was government money.There are extensive gardens on the grounds, which formerly were occupied by operations of the mining concern.

Guanajuato has a soundtrack all its own: every museum seems to have at least one room with a smoke alarm, high in the eaves, which chirps expectantly periodically; our Sunday morning quiet was shattered by the boom of 5 blasts of a cannon at 7 am, apparently summoning the faithful to church; even our room, with a domed bricked ceiling with a central cupola, reverberated with a nightly fluttering. The first night, I imagined this was a trapped tiny bird, beating its wings frantically trying to escape. I hoped it was not a bat. It proved to be a huge moth, which seemed not to be able to escape, despite being able to fly.

Monday, November 24, 2014

Javier the gardener was watering plants in the courtyard when I emerged for the morning. He beamed when I told him I had heard he was a good singer. Later, he serenaded us in the dining room with two powerfully belted ballads, Amor Eterno and La Unica Estrella. A sample of the lyrics from Amor Eterno, with my rough translation following:

Tu eres la tristeza de mis ojos (You are the sadness in my eyes)

Que lloran en silencio por tu amor (That cry in silence for your love)

Me miro en el espejo y veo en mi rostro (I see myself in a mirror and see in my face)

El tiempo que he sufrido por tu adiós (The time I suffered your departure)

Obligo que te olvido en el pensamiento (I have to forget you in my thoughts)

Pues, siempre estoy pensando en el ayer (But, I am always thinking of yesterday)

Prefiero estar dormida que despierta (I would rather be sleeping than awake)

De tanto que me duele que no estés (It hurts so much that you are not here)

One of the few museums open on a Monday was Museo de las Momias, or the Mummy Museum. This unusual museum was immortalized in the 1972 film, Las Momías de Guanajuato. This is an offbeat offering, more than a little creepy, but very unique and unforgettable. The town’s cemetery filled up in the 19th century. If a corpse’s descendents couldn’t pay the required tax, bodies were disinterred to make room for others. Many were found to be remarkably well preserved, some including their shoes and stockings, apparently due to the soil’s mineral content. They were macabre, with a collapsed, dehydrated appearance.

Afterwards, we walked in the adjacent cemetery, the Pantéon, which had drying flower arrangements left over from the recent Dia de los Muertos observations. (For an account of Dia de los Muertos in San Miguel de Allende, here is a link: https://aperturephotoarts.com/san-miguel-de-allende-dia-de-los-muertos-2013/ )

On the way down, we passed the old train station, La Estación de Ferrocaril, where a young girl was spinning around with a round basket, exciting the attention of a flock of pigeons nearby. Thinking she was feeding the pigeons on a large scale, we followed her into her family’s food stand, where Steve made a new friend and we found a photo subject, using a new toy, a retro-looking Fuji camera that spits out business card size miniature Polaroid-like images that develop in a few minutes.

Before venturing into the giant, Gustave Eiffel designed Mercado Hildago (an early form of pre-fab construction), we had lunch across the street at Tacos El Paisa.

Four small tacos al pastor each, on house made corn tortillas, and we were able to brave the marketplace.

Randy left us for the grocery store, while Steph, Steve and I took a meandering route back, via the Basilica de Nuestra Señora de Guanajuato.

We lucked into running into a splendidly outfitted mariachi band playing in the street, to a mysterious patron on the second floor of the Hotel San Diego restaurant.

La Catrina, a “delightfully sugary” distraction drew us in with its colorful offerings. The charming young salesman plied us with samples, selling us on unusual snacks and salsas we never would have tried otherwise (sadly, my oil, walnut and chile salsa was apprehended at the airport, being deemed too liquid-y and too big to be carried on).

Arriving home, Randy had whipped up a tomato salad and shrimp and leftovers pasta dish, perfect for relaxing and recuperating cobblestone worn feet.

Tuesday, November 24, 2014

Randy headed out early in search of lamb shanks. After his return, we set off late morning to the Teatro Juarez, in advance of meeting the housesitter, Catherine, of their friends, Jan and Ren, there at 1 pm for a key handoff.

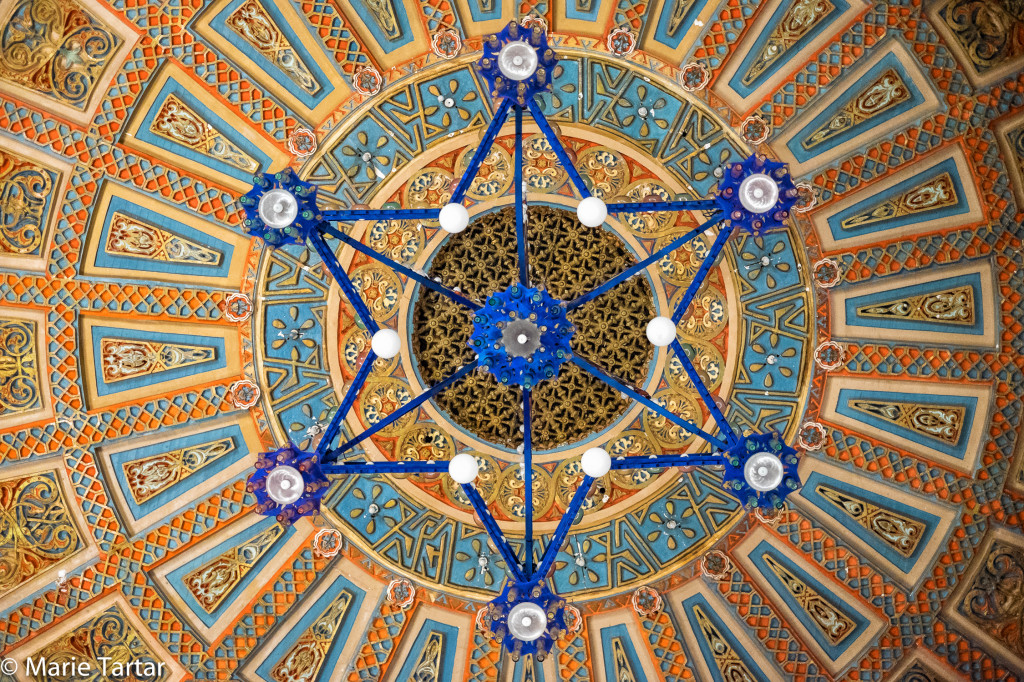

Spectacularly decorated ceiling of Teatro Juarez. The huge chandelier apparently fell during installation, killing workmen. The story goes that a similar incident occurred at the same time at the Paris Opera.

The Teatro is Moorish in style, elaborately decorated. Catherine was meeting a whole group of friends for lunch, so we had a chance to meet them before heading off in different directions. We flagged down a cab for our return to Marfil. Randy and Steph had stayed previously in this house and thought we would enjoy seeing it. It proved to be a delight, with butterflies dancing in the terraced gardens, huge sculptural agaves, and inside, museum-worthy folkloric collections, beautifully complementing the Gene Byron tile-topped tables and wonderful built-ins. The house was designed by architect Manuel Parra for Canadian artist Gene Byron and her husband Virgilio, who still lives nearby. They built it for themselves, but never moved in. Randy and Steph’s friends have gradually made very sensitive improvements and additions to the structure and restored the overgrown gardens. We lunched on carnitas tortas from the near-by stand up on the roofdeck, with an incredible view of the Templo Santiago de Apostle. The house is easy walking distance to Museo Gene Byron, created post-humously by Virgilio as a tribute to his wife’s wide-ranging artistic career, in the Ex-Hacienda Santa Fe, in which they lived since the early 1960s. Seeing this beautifully appointed and maintained private home first was the perfect complement to seeing her longtime house and studio turned museum afterwards.

We made it to the museum 10 minutes to closing, but the staff member patiently showed us around, including the casita.

At the concert a few days earlier, we had been able to peer through the windows at the living quarters, enough to know that we wanted to see the inside. Beautiful details abounded, and we recognized many Gene Bryon touches in common between the two houses. Gene Byron hand-painted tiles with imaginative animals adorned the bathrooms and kitchens. There was a selection of her paintings, as well as mid century styled ceramic and metal works.

Afterwards, Steph, Steve and I headed to the Diego Rivera Museum, which is in his upper class family’s home and where he spent his first 6 years. In addition to rooms furnished in the style typical of the era, there is a collection of predominantly early works of his, donated by Marte R. Gómez. It was interesting to see Rivera’s early artistic evolution in Paris, where he clearly was trying on a variety of artistic directions, with Renoir-rotund portraits, Monet-esque landscapes and Cezanne-resembling still lifes.

The museum also presented work by contemporary portraitists, the most arresting of which was Territorios de Luz, startlingly intimate and penetrating portrait paintings and drawings by Virginia Ledesma.

We dined out at Mestizo, a favorite of Randy and Steph’s, and we all enjoyed ourselves. We shared ceviche to start, and I had salmon, crusted with pepitas and huitlacoche, the corn fungus prized in Mexican cuisine for its unique smoky, mushroom flavor. The chef and owner is the son of celebrated local ceramic artist Capelo, whose work was prominently on display.

Wednesday, November 12, 2014

For our final day in Guanajuato and an early Thanksgiving, Randy planned an all day long culinary grand finale, for which he had laid the groundwork the prior day, procuring pork shanks from the butcher. Before Steph, Steve and I headed out at the crack of 11 o’clock, he sautéed them in olive oil and garlic, browning and braising them on all sides, and dusting them with salt, cumin, cardamom, and “Joe’s stuff” from New Orleans. Then it was into the oven at 350 degrees for the rest of the day, with potatoes, carrots, onions and eventually cauliflower added later. While Randy babysat the “stinko,” a dish they first encountered while in Umbria, we headed into El Centro to the historic La Alhóndiga de Granaditas, a neo-classical rectangular building where critical early events of Mexican Independence took place. Originally a granary, the building has also had lives as a prison and now a museum. In 1810, Spanish loyalists holed up with their silver inside the fortress-like structure, expecting relief from reinforcements. A miner known as El Pípila led Independence-minded rebels (indigenous peoples, the poor, miners) in a charge on the building, shielding himself from volleys of Spanish royalist bullets by carrying a large stone on his back. He was able to breach the fortress by setting one of the wooden doors on fire. This was the bloodiest battle of the eventually successful independence from Spain. But before this was successfully won, the local rebellion was quelled and the heads of 4 leaders of the rebellion were displayed on the corners of the building, where they hung for 21 years. There are still hooks and stone plaques commemorating the martyrs at each corner.

The Alhóndiga is an interesting museum, with galleries devoted to pre-Columbian art, including inscribed sellos, or seals, used to sign documents. I again loved the turn of the 20th century painted portraits of the regional notables by Hermenegildo Busto, whose work we had first seen a few days before at Museo del Pueblo de Guanajuato. Downstairs, we all loved a show of black and white photography of Rodrigo Moya, a photojournalist born in 1934. In the courtyard was an exhibition of sculpture, including large works of Capelo, whose chef son we had met a few nights earlier at Mestizo. Best of all were large allegorical frescos by José Chávez Morado filling several stairwells.

José Chávez Morado murals fill stairwells at La Alhondiga de Granadita in Guanajuato, and allegorically depict events of the Mexican Independence from Spain

Steph and I had a good time deciphering the iconography before checking our interpretations against the officially provided ones (por supuesto, en español).

We had a late lunch at La Vela (which means sail, or candle), a mariscoría or seafood restaurant. One of the Crafty Ladies had mentioned it to Steph the day before as having good empanadas. Steph and Steve each opted for two of the sizable empanadas, one tuna and the other marlin, while I went with the waitress’ marlin tacos recommendation. The meat was unusually red, savory and very tasty. We had a great view of the domes of the Templo of San Diego from under our umbrella-shaded perch outside. Periodically, great waves of pigeons would stir around the domes.

We were near a tunnel entrance, perfectly positioned for flagging down a cab to take us up to Pastita, not to be confused with Pastitos. Our destination was the home turned museum of Olga Costa and José Cháves Morado, Casa de Arte Olga Costa-José Chávez Morado, whose work we had been seeing at the Museo del Pueblo and whose murals adorned the Alhóndiga. In addition to donating their home to become a museum in 1993, this art power house couple donated their collection of pre Hispanic, colonial and folk art to the museum of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas in 1975, and founded the Museo del Pueblo de Guanajuato with 18th and 19th century pieces from their private collection. Casa de Arte was formerly a tower of an hacienda, adapted by the couple into a charming abode filled with their collectibles, adorned with stained-glass windows of their own design and with a small gallery upstairs with examples of their paintings and tapestries.

The interior of Casa de Arte-Museo Olga Costa-José Chávez Morado is filled with their folk art collections. This type of brick-lined barrel vaulted ceiling is a frequent feature of residential architecture in Guanajuato

In another pair of galleries were lithographs of multiple different artists paying homage to a recently deceased poet, Efrain Huerta, in a show called Cien Años de Perdón (100 Years of Pardon).

Perched on the stairs, a friendly staff member plied us with information (in rapid but marvelously clear Spanish) about the lives of these 2 artists who met in Mexico City while students at art school in 1933. They married when she was 21 and he 26. She emigrated from Germany to Mexico with her family at the age of 12, her father fleeing a death sentence. She shortened her Russian-Jewish name to Costa to sound more Mexican.

The museum was a wonderful start to a scenic walk back down to El Centro, winding along a tree-shaded waterway and along the recently pedestrianized and pleasant Embajadoras.

Back in the Centro, we checked out a French bakery new to Steph, La Vie en Rose, and I resisted the temptations of a transplanted Japanese jeweler, before climbing back up the hill as darkness descended.

The “stinko” smells, make that aromas, were intoxicating as we arrived back to the house for a Thanksgiving scale feast. In time-honored Thanksgiving style, it was difficult not to overeat, the meat falling off the bone, with a crusty aromatic glaze and the vegetables infused with the drippings. This would have been more than sufficient, but Randy also made a delicious tomato and avocado salad for contrast. A feast for the nose, eyes and palate, it was a sumptuous send-off.

Randy had arranged a 6 am pick-up with Gabriel, a jewelry maker (and brother of Hugo, an artist and print-making instructor). We had been in Gabriel’s store a few days earlier, where another valiant struggle to resist temptation was won with difficulty by me. This morning wasn’t as cold as on our arrival, but the airport itself made up for it. Even Steve (who is essentially NEVER cold) was freezing. I noticed all of the staff were wearing coats inside. The comparatively warm plane was a relief.

Of course, our memories of this special place, so wonderfully introduced to us by our gracious hosts, will long continue to warm our hearts. Randy and Steph have a strong preference for Guanajuato over San Miguel de Allende, as more authentic, less gringo overrun, and we can definitely see its allure.

Not that everything is sweetness and light in Guanajuato, although that is all that we saw. Prior to our departure, we were surprised to receive an email from Randy saying that since their arrival, they had learned of several disturbing incidents and felt we should be aware. His email was sobering, indicating there had been

“… a couple (of) home invasions here in the last year, both pretty scary but everyone survived. The culprits from the second invasion were caught and are now in prison, but the first intruders are still unknown, though it could have been the same gang.

The first invasion was a year ago, in the house in which we are now staying. Though we feel safe here, and there have been extensive security improvements, we felt we should let you know about these events so you could make your own judgment about whether you wanted to continue with your plans to visit.”

Steve and I were not dissuaded, reasoning that home invasions are rare, and even happen in La Jolla. It was disturbing to learn while there of an incident involving a neighbor walking alone in the countryside with her dogs, who was shaken down for money and left chained to a tree. She managed to free herself and wasn’t harmed physically, but no longer feels free to walk alone in the backcountry, as had been her wont.

It was a little hard to assess whether this “crime streak” is an aberration or a trend. We’ve heard that even drug lords need a safe place to vacation with their families, and that Mexican tourist-favorites Guanajuato and San Miguel de Allende are “safe havens” which have been largely spared the violence that puts the spotlight on Mexico in the headlines.

The house in which we were staying, belonging to friends of Randy and Steph’s, was beautiful and comfortable, tastefully more fortified than on their prior stay, with higher stone walls and more decorative grillwork on windows and doors.

We would not have known by looking that this was a response to a scary invasion. Presumably, the owners were targeted as having money, and although there is a large middle class in Guanajuato, there clearly are great divides between rich and poor. Chatting with the housekeeper, Leo, one morning, I learned she commutes by bus 1 hour each way and does her own laundry in a river, not having running water where she lives. She doesn’t do laundry in the washing machine, which seems to intimidate her, suggesting she isn’t literate. But she was warm and sweet and open to talking about her life.

Even a casual analysis of the transportation options in Guanajuato suggests the great economic divide among us. Randy and Steph have utilized all options, and had rented a car on a prior extended stay. In Guanajuato itself, especially in the historic center, many roads are one way, others open only to pedestrians and a car generally is a liability. The tunnels provide some parking for cars.

Guanajuato’s tunnels shunt most car traffic underground, below the historic center, and provide some space for parking

Subsequently, Randy and Steph have managed without a car, using a combination of walking, buses and taxis. Taxis are priced very reasonably, at least on the Gringo scale, with fixed rates within the city (generally, 35-45 pesos, depending on the distance, about $3 US). While that is cheap by Gringo standards, it is expensive compared to bus fares, at 5 pesos per ride. In general, the bus system seems to be the local’s transportation, while gringo residents and tourists can more readily afford cabs. Randy and Steph often set out for more distant (and often elevated) destinations by taxi, then walk back, generally downhill. They have even made excursions as far as Mexico City by bus.

For us, we found a lot to like in Guanajuato. Much of what we had admired in San Miguel de Allende the year before was also present in Guanajuato, namely colors, textures, sun, blue skies, a lively cultural scene, and music. Guanajuato has a youthful energy imparted by being home to the University of Guanajuato, the Harvard of Mexico. Expats are a minor presence in Guanajuato, making up less than 1% of the population, vs. 10% in San Miguel de Allende. Guanajuato struck us as somewhat grittier, or perhaps we just had a more nuanced view of life there, having the benefit of our friends’ longer stays and greater experience. We found strolling its narrow alleys a visual delight, with unusual juxtapositions of colors and textures, as though the buildings themselves were giant abstract artist’s canvases.

Of course, there was street art, as well garden variety graffiti. A couple of my favorite entries in the street art category:

So many details to enjoy, too little time. A few of my favorite carved doors:

A visual feast, with a soundtrack all its own, and the companionship of great friends, we couldn’t have asked for a better introduction to the glories of Guanajuato!

-Marie

Bravo for the striking photos and words! A definite add to my travel list, and a place I was totally ignorant about until you enlightened me. I can feel the warm colors and taste the tortas.

Hi, Marie. What amazing photos. What an eye you have!

Hope you plan on returning to San Miguel.

All best,

Kathy

Oh, Marie! What terrific images – thanks for sharing!

Deliciosa! The colors and textures make me want to dip a tostada chip into the frames of these masterworks as if they were made of salsa picante. Very well done, my friend! Bravissima!

thank you to Pat who shared this diary with us while we are ourselves exploring Mexico now – and had not yet determined which places were still the REAL think, vs the “expat” world… With your wonderful details, we will make this trip to expand our experience!! thank you!!