I Ran over My iPad, My Mother Died, Then the Shit Got Real:

An illustrated autobiographical tragicomic novella in 10 chapters

by Steve Eilenberg

Part 3: The Dead Husband Club

Mary dropped out of her water aerobics class at the YMHA to look after David’s needs. Calls from her pals trickled down over the next few years. Most of their husbands were already dead, so Mary was a bit of an anomaly.

She would occasionally lunch with these water aerobics friends, at their senior living complexes. During these social calls, Mary would note their closet space, bathing facilities, number of stairs, meal quality and landscaping. Most of these senior living complexes required near total transfer of assets, which would be whittled down, until they either died or were too destitute to remain. Mary worried about live-in daughter K. She was too young to move in to a senior facility with them, and besides, they didn’t get along. Mary knew they could not afford to maintain 928, AND move into a senior living situation. This paralyzed Mary’s decision making.

Mary was now diabetic, and losing weight. Her shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles were shot. She scooted around on her favorite, all-terrain, four wheeled, “pretty” red rollator. It had a flip-down textured seat and brakes and was the perfect height for loading and unloading the dishwasher, but wrong for just about everything else in the house. The only bathroom on the main floor was the diametric opposite of ADA, but was still cherished, because it had a pink toilet, sink and bathtub from the 1950s. The sink was cracked and glued together with bone white silicone. The toilet, the one I potty trained on, was too low and flushed languidly. The bathtub was high walled and slippery, with at least 4 grab bars. Shockingly, a couple of them were actually firmly attached.

Sarah and I took Mary out shopping for new fixtures at a drab shop she heard about near Newark, New Jersey. I think it is where plumbers went to replace budget fixtures for nearby row houses. Shunning the few dusty floor models, and with the aid of relatively current catalogs with pages as thin as a telephone book, we outfitted her new bathroom on paper. Still too small for a wheelchair or a rollator, it was better than the current deathtrap. Mary lamented that it wasn’t pink.

No repairs, changes or additions at 928 ever happened quickly. When the family moved there in 1959, much of the first floor was given over to David’s medical office . This left the second floor, as a 2 bedroom, one bathroom house, for my parents and their 4 children. With few possessions, allowance or privacy, they put 4 of us in one bedroom. Sarah in a crib, me in a top bunk, and Susan in the bottom. K, the bed-wetter, was on a folding cot. Inexplicably, I acted out and was banished to the dusty, dark, bare, cinderblock and open beamed basement. In my new digs, I would lie there and worry:

“The office is just beyond this wall…what does my father do? He is a doctor and sees sick people. What do sick people do? They get better or die…”

Way before computer games, kids of my generation glued airplane and car models together. Sometimes, I left parts out. I hid these mistakes in the trunk of the model and glued it shut. The models rattled, but I appeared to be a competent builder. In my young mind, I thought my father might do the same with his dead patients. I seldom saw ambulances at the house and never a hearse. It made sense to me that he might hide away his mistakes too…his dead patients …stashed away somewhere in this very same basement.

I had a horrifying thought:

“What if my father threw away patients that just looked dead, but weren’t?”

Surely things like this happened from time to time. Every noise at night, I was sure was one of these not quite dead patients, trying to free themselves from a garbage can in which they were stashed.

My basement internment was meant to be temporary. My parents, mostly my mother, were working on an addition with a local architect, Adolph Cucci, for years. Mary’s vision of a third floor addition went something like this: Put Sarah and K in one bedroom. Why? Because they hated each other and this would force them to get along. Susan would get her own room, as would I. The three bedrooms would be serviced by one bathroom. Why? So we would learn to share. This left space for a large common space, which would house a ping pong table. Why ping pong? It was lighter and less expensive than a pool table and the kids would learn to play together. While horribly flawed, the plan was simple, but it still took the better part of a decade to be realized. Starved for personal space and with construction about to commence, Susan, K and I climbed a wooden ladder into the attic, through my mother’s closet, to claim our future bedrooms. Between squirrel feces allergy, rafter splinters, and rashes from the pink fiberglass insulation, we were a mess. Still, there we were. Almost in our rooms, protecting our turf, barking at the others to “GET OUT OF MY ROOM!”

My mother’s timeline for the house addition was my bar mitzvah, but it was looking more like Susan’s high school graduation. At least we would have our own bedroom, when visiting from college and beyond.

The third floor addition didn’t fare too well over the years. Windows stopped operating, balcony doors would blow open with little provocation, vinyl siding was cracking and the balcony floor developed holes and soft spots. Susan’s room developed toxic mold and the shower leaked behind the tile. Twenty years later, a house fire, which started in K’s room, took out this addition and the attic above. To everyone’s great relief, the Boehm porcelain birds were unscathed.

The house fire deserves special mention as it is the poster child for an Eilenberg black comedy. So the story goes, a garage sale floor lamp was being held up by piles of clothes and stolen library books in K’s room. Perhaps it was a bad cord or an unsteady base; either way, the lamp was the smoking gun. K claims to have no sense of smell, in spite of her habit of picking up everything and putting it under her nose. So, it must have been either my mother or father who first smelled smoke. One of them responded by flipping the switch for the giant attic house fan, effectively adding fuel to a simmering flame. It being dinner time, the three sat down for “slop,” as my father called it. Let me interject that my father had a “delicate stomach” and could not tolerate anything stronger than low sodium broth. There was no onion, garlic, salt, pepper or olive oil involved in the cooking for David. Truly what he ate was slop, David slop. Not Mary’s slop.

As dinner progressed, the fire started lapping through broken windows on the third floor. Neighbors, who would never just drop by, were ringing the bell and pounding at the back door. With annoyance, Mary or K (never David) answered the door. An agitated neighbor, wildly gesticulating, told them the house was on fire. They were firmly told: “No, it’s not.” The door was closed and dinner continued. Pounding continued and police and fire engines arrived. Our cousin Eric was on the volunteer fire force and helped put out the fire. David was from then on known by the local fire and police department as Doctor Housefire. I assume it was a play on words from Mrs. Doubtfire, the film starring Robin Williams.

The insurance settlement was swift and the house rebuilt exactly as it was designed 20 years earlier, including the heavy gold textured drapes, the single bathroom, but this time, no ping pong table as they are “too flammable”.

The 60 inch old style TV survived the fire, but was melted to a form recalling Jabba the Hutt. The paintings were restored, probably by a 5 year old with crayons and magic markers, and the naugahyde couch was replaced by one with even stickier cushions. K’s sodden, burned, stolen library books were quickly replaced with new stolen books and the offending floor lamp was rewired and replated. K eventually took ownership of all three bedrooms on the third floor, filling them with things one might find under a Los Angeles overpass, minus the grocery cart. Mary’s knees were in such sorry shape, she seldom had occasion to see K’s transformation of the third floor addition.

(The melted TV set looked like Jabba the Hutt. “Return of the Jedi” 1983)

(The melted TV set looked like Jabba the Hutt. “Return of the Jedi” 1983)

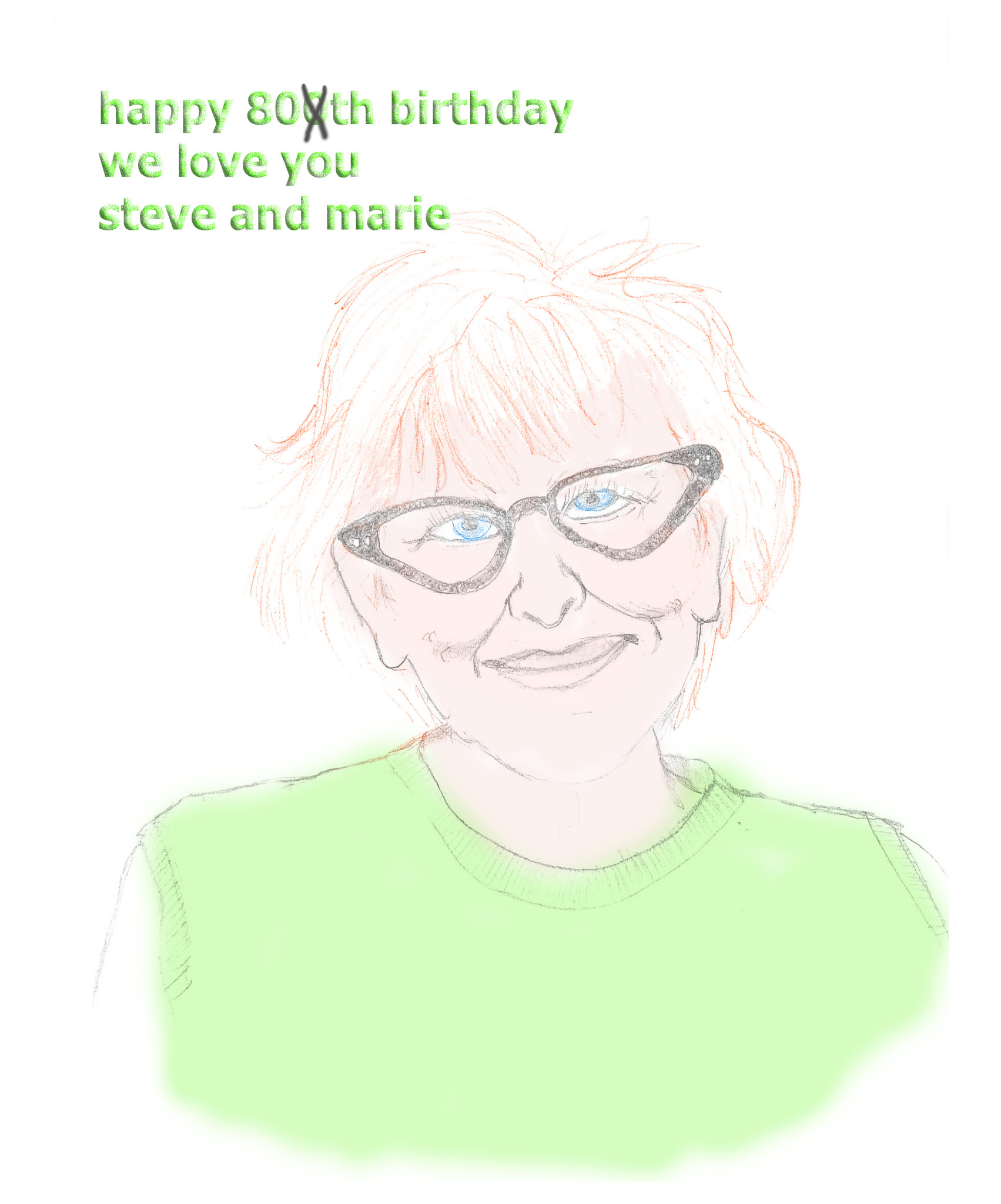

In July, 2010, I flew back to celebrate my mother’s 80th birthday. I didn’t do the math, but my father was now 90 and my mother was always 10 years younger than my father. All the kids and their dogs came for the weekend. We spent the morning shopping with Mary in Upper Montclair for our gift to her: “fancy” new eyeglasses.

(Mary thought these were pretty fun)

(Mary thought these were pretty fun)

Later that day, we set up a feast outside, on the back patio. Food came from a favorite local Italian market, A & A Deli, and Sarah made my mother a dietetic dessert decorated with many candles. Mary was radiant that night, with all her children around. At the evening’s end, she told us that she was 79, not 80, but thanked us for coming anyway.

(Mary at her 80th, woops 79th, birthday party. New glasses were not ready yet)

(Mary at her 80th, woops 79th, birthday party. New glasses were not ready yet)

I have a picture of my father from that evening. Sitting there, looking sad and dejected. I don’t know if he was jealous of Mary or if Parkinsonism caused his face to distort into a sad snarl.

(Before the Party: David at Mary’s 79th birthday)

(Before the Party: David at Mary’s 79th birthday)

On the last evening of this trip, I sat at the kitchen table with my parents and Sarah and asked my father if he had a living will and advanced directives. He was, after all, 90 years old, nearly died a few years earlier and a retired physician. He found my questions amusing and he was characteristically evasive and unhelpful. In desperation, I presented him with scenarios to at least get some sense of his preferences. This man was a lifelong hypochondriac, who would hold his breath and run from a room if someone sneezed. Paradoxically, I might add, this same man would save a nickel in a public restroom by having mini-me crawl under the stall door of a pay toilet to let him in.

The conversation went something like this:

Me: “OK, you fall down in the kitchen and break your hip. What would you want done?”

David: “I’d want you to leave me in peace.”

Me: “So, no ambulance?”

David: “Just leave me be”.

Me: “No surgery?”

David “No.”

Me: “Carry you to your bed?”

David: “No.”

Me: “Would we feed you? Give you water?”

David: “Some water would be nice.”

(As we spoke about advanced directives, we ate pistachio nuts and I embellished the shells and photographed them on a napkin.

(As we spoke about advanced directives, we ate pistachio nuts and I embellished the shells and photographed them on a napkin.

From left to right: Steve, David and Mary)

I told him he was not being helpful and that it was selfish of him not to have explicit directives. Angry and frustrated, I grabbed my suitcase and decamped to a nearby motel. As I was leaving, I heard him in the background saying: “Just run away! Run away to your hotel!” On my way to the complementary waffle breakfast the next morning, I understood. David wanted comfort care and no heroics, but I guess that was too difficult to say or formally memorialize with advanced directives.

The next year, West Nile fever was lapping at the door of 928 and the only thing luring them outside was Costco. I told my father once that Costco is “not a real hobby.” He told me I was wrong. Mary and David had reached geriatric homeostasis, when it happened.

Coming Soon: Part IV “The Broken Stick”

Steve, these are funny, brilliant and sensitive. I’m pretty sure we all lived inside one long Seinfeld episode!

Steve,

Thank you so much! for sending me these absolutely hilarious writings of yours. I can’t stop smiling and laughing. Excellent!- Now more please!

Susan